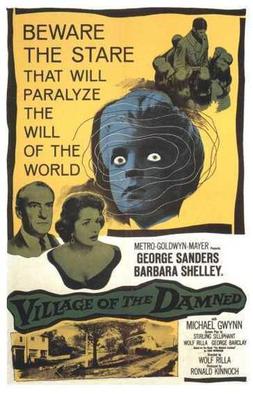

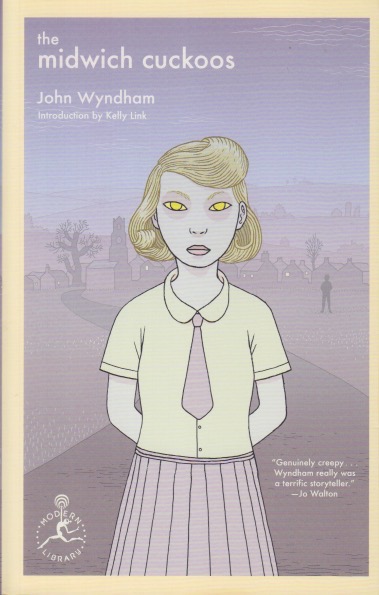

If I’m honest I’ll admit that I first found out about John Wyndham’s The Midwich Cuckoos from The Simpsons. In one of the episodes, “Wild Barts Can’t Be Broken,” a “clip” is shown of a horror movie called The Bloodening. A spoof on Village of the Damned, the scene caught my imagination and I was able to learn that it’d been taken from this movie. This was many years ago, of course. In any case, I went out and found a DVD of Village and found it less frightening than anticipated, but it left me curious. It was easy enough to find out the book it was based on (it’s in the credits). Now, well over a decade later I finally read it, but I’d forgotten nearly everything about the movie but the glowing eyes. Having read the novel, I had to see the movie again.

Interestingly, the book is generally considered science fiction and the movie horror. The two genres are closely related, of course. The explanation for the children in the movie is a little sci-fi, but the framing is horror. So much so that in Britain in 1960 it was nearly given an X rating (the censors didn’t like the glowing eyes). As typical, when compared to today’s fare this is a tame little piece about some unruly children. Of course they do get blown up at the end. That may have been a spoiler. I guess I can be unruly too. In any case, sequences of self-harm, and even suicide, make this a reasonably scary movie. The film has the same stiff upper lip that the book does, but otherwise it’s a modern horror classic. I haven’t seen the 1995 remake, but it didn’t get very good reviews.

The movie doesn’t have as much moralizing as the novel does, but it raises the very real issue of how we socialize children. I do suspect, however, that blowing them up when they’re all together is probably not the message they wanted us to take home. Although far from a flawless film, this is quite intelligent for horror of the period. Consensus is that horror “grew up” in 1968, but there were some premies, it seems. Night of the Demon is another one from the period. Horror has, I would argue, been intelligent from the start. Dracula, although not a perfect story, has become a bona fide classic, and Frankenstein before it, had already been a literary touchstone for decades by the time the former was published. Not bad for watching an episode of The Simpsons.