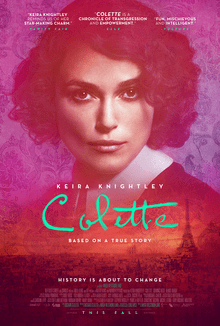

Despite AI, one of my great regrets is not having learned additional languages in high school. I took four years of German and the one classmate I knew who was able to convince the administration took two languages, both Spanish and French (gasp!) to become a translator. In any case, I regret being able to read French only haltingly, with a dictionary. I watched Colette because it is the biopic of a writer, but I’ve never read any of her books. I also watched it because it’s considered dark academia, but you already knew that, didn’t you? Colette lived from the last quarter of the nineteenth until the mid-twentieth century. Her first husband published a successful series of books she wrote under his name. The two separated and Colette went on to become a reasonably successful writer in her own regard.

As with most biopics, the details are exaggerated, but still, this is the world of books where fiction and fact aren’t always so far apart as might be supposed. Interestingly, articles on her husband (Henry Gauthier-Villars), known by the pen name Willy, state that he is best known as the first husband of Colette. A self-promoter, he had other people do his writing for him. The movie focuses on what happens when he tried to bring his wife, not yet established in her own right, into his band of ghostwriters. Not having French, I have never really studied French literature. If life allowed a bit more time, that is something I’d like to have done. In any case, Willy was a libertine as well as a self-promoter, the sort that occasionally enters high government position. And since he was involved in many affairs, Colette explored relationships with other women. In other words, this is a story that is still very relevant.

Dark academia sometimes involves a literary life rather than a strictly academic one. I applaud its love of books and book culture. Some of us miss the days when it was possible to have publishers eager for new material, when books were generally respected instead of widely banned. The darkness here is clearly the manipulative relationship Willy has with Colette. He uses her lack of experience in the publishing world to his own advantage, and habitually making poor financial decisions, puts their living situation and security at risk time and again. I sometimes wonder about my high school friend. Did she become a translator? And, if so, is her job, nearing retirement age, under threat from AI? And this, in the span of a human working life. A life of books.