Music preserves your youth. When my wife was studying music therapy, one of the pieces of information she received is that those whose brains have begun to shut down the speaking faculties can still sing. People respond best, in such states, to the music of their youth. Anyone who lives long enough will decry the noise that the younger generation calls music. I’m thinking about this not just because of my recent visit to Bethel Woods, but also because of a New York Times story that Paul Simon is planning to leave the musical stage. Simon and Garfunkel was among the music of my youth. Accessible music with profound lyrics and, for the most part, a muted sadness. I grew up a long way from New York City, but listing to this music I felt like I was wandering the streets of the Village, soaking in a reality I would otherwise never experience.

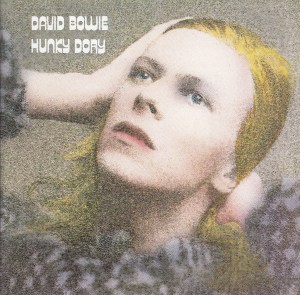

It strikes me as no surprise that among the earliest manufactured artifacts discovered are musical instruments. While I seem to have missed nature’s boon in offering musical gifts, I nevertheless inherited the appreciator’s side. I don’t often listen to background music. I listen to music to listen. It carries its own meaning, akin to what we tend to think of as a religious experience. No doubt, for many, Woodstock felt like such an encounter. Music that could take you away from the troubles of a war-torn, prejudicial, jaded society. Even if only for a few moments. “I am a Rock,” was, for much of my youth, a kind of personal anthem.

During a commencement address in not too distant months past, Simon told the graduates that ours was becoming a society at war with art. Music is money. College isn’t about becoming who you are; it’s career training. We don’t allow our young any time to explore any more. Few are willing to admit that capitalism, unrestrained, is just as bad as communism. Music used to be about the soul. The artists I know tell me it’s now about the cash. The man calls the shots. So as I stood on the hill overlooking the former Max Yasgur’s farm a few days ago, the lack of sound was poignant. There used to be, it seemed, different ways of existing in the world. Today the tempo is set and the music composed by those who prefer marching tunes that lead straight to the bank. Standing on that windswept hill I’m sure I can hear the sound of silence.