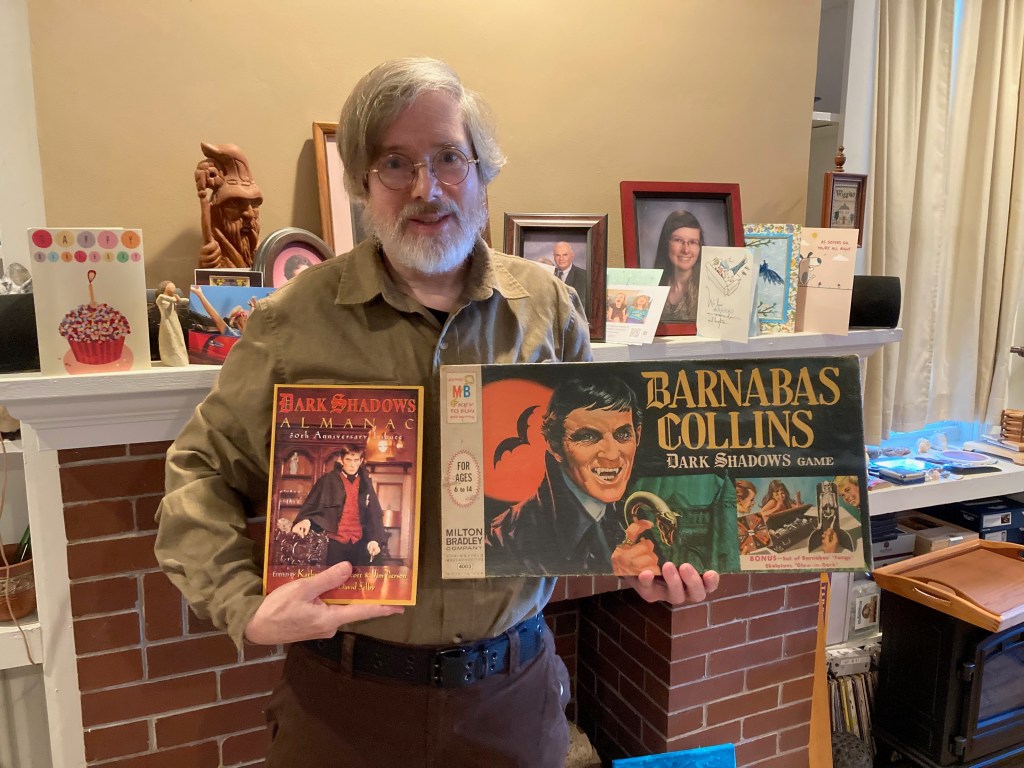

A friend’s recent gift proved dangerous. I wrote already about the very kind, unexpected present of the Dark Shadows Almanac and the Barnabas Collins game. This got me curious and I found out that the original series is now streaming on Amazon Prime. Dangerous knowledge. Left alone for a couple hours, I decided to watch “Season 1, Episode 1.” I immediately knew something was wrong. Willie Loomis is shown staring at a portrait of Barnabas Collins. Barnabas was introduced into the series in 1967, not 1966, when it began. Dark Shadows was a gothic soap opera and the idea of writing a vampire into it only came when daily ratings were dismal, after about ten months of airing. Barnabas Collins saved the series from cancellation and provided those wonderful chills I knew as a child. But I wanted to see it from the beginning.

I’ve gone on about digital rights management before, but something that equally disturbs me is the re-writing of history. Dark Shadows did not begin with Barnabas Collins—it started with Victoria Winters. There were 1,225 episodes. Some of us have a compulsion about completeness. The Dark Shadows novels began five volumes before Barnabas arrived. Once I began collecting them, I couldn’t stop until, many years later, I’d completed the set. I read each one, starting with Dark Shadows and Victoria Winters. Now Amazon is telling me the show began with Barnabas Collins. Don’t get me wrong; this means that I have ten months of daily programming that I can skip, but I am a fan of completeness.

You can buy the entire collection on DVD but it’s about $400. I can’t commit the number of years it might take to get through all of it. I’m still only on season four of The Twilight Zone DVD collection that I bought over a decade (closer to two decades) ago. I really have very little free time. Outside of work, my writing claims the lion’s share of it. Even with ten months shaved off, I’m not sure where I’ll find the time to watch what remains of the series. The question will always be hanging in my mind, though. Did they cut anything else out? Digital manipulation allows for playing all kinds of shenanigans with the past. Ebooks can be altered without warning. Scenes can silently be dropped from movies. You can be told that you’ve watched the complete series, but you will have not. Vampires aren’t the only dangerous things in Dark Shadows.