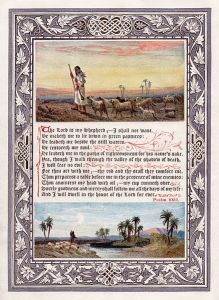

Four centuries ago this year William Shakespeare died. In the literary world there have been lots of commemorations going on, and all the fuss reminded me of a post I’d written some years back concerning Psalm 46. While teaching at Nashotah House, one of my students told me that William Shakespeare had covertly been involved in the translation of the King James Bible. The King James Version appeared in 1611, and Shakespeare was the prominent writer of England in that era. If you look at Psalm 46 in that version and count the 46th word from the beginning, you find “shake,” and the 46th word from the end is “spear.” I mentioned in my post that I’d not found any academic treatment of the issue and I’m happy to announce that I finally have. Of course it would be in an Oxford University Press book.

I’ve not read Hannibal Hamlin’s The Bible in Shakespeare, but I am able to glance through it at work. It turns out that I didn’t have the full details of this biblical urban legend. Apparently if you find the sixth and seventh words of verse 10 of that Psalm you find “I am.” The sixth and seventh words from the end are “will I.” Will.i.am would be proud (pardon the capital W). As much fun as all this evangelical exegesis might be, Hamlin calls shenanigans on it all. He demonstrates the literary history of the tale, pointing out that—not to spoil our fun—the cryptographic mentions of the Bard in the Bible are creative efforts of those of later generations. The interesting thing is, however, that the Bible is so closely scrutinized for codes that all kinds of hidden messages may be found. Look, for example, at what I discovered:

“For the Lord himself shall descend from heaven with a shout, with the voice of the archangel, and with the trump of God: and the dead in Christ shall rise first.” I don’t know about you, but to me this is clearly Paul warning the first Thessalonians of the present day’s troubles. When Trump is elected the dead will walk. Could anything be more prophetic than that? I haven’t done the math yet, but I’m just sure if you count the millions of letters in the Bible, you’ll find the name “Donald” spelled out somewhere. Scripture, after all, is the repository of all truth. One thing you won’t find, however, no matter how deeply you look. The billionaire’s tax returns are something God himself will never be able to see.