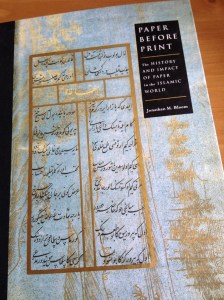

My heart goes out to academic authors. It really does. They labor over a book important to their field and see it come out costing near triple digits and wonder why it’s not in the local bookstore. There is, however, a very wide gap between academic and trade publishing. It is bridged here and there by authors who value readers over reputation, but unless you deliberately try to learn how all of this works, it is bewildering. Academics, you see, are area specialists by and large. You don’t write a dissertation on the Bible, for example, but on a specific part of the Bible (New Testament or Hebrew Bible). And within that section your specialization is not a single book, but often a small part of a book, or a theme. I’ve seen dissertations written on a single Hebrew word. Specialization.

With all of this tight focus, it’s easy to forget what browsing in a bookstore’s like. Even with some of the incredible brick and mortar stores in Edinburgh, technical books had to be ordered—this was before Amazon. When you check the books of colleagues out of libraries it doesn’t always occur that you do this because libraries are the only places that buy such books. And with the explosion of doctoral degrees in shrinking areas of studies (there are no jobs here, folks!) the number of published dissertations has skyrocketed. Even advanced scholars forget the average reading public would find their work impenetrable. It’s not going to be in the local bookstore, and it costs so much because it sells so few copies. I do feel for academic authors.

In addition to all the area specialization, it would make sense to research the academic publishing industry. Yes, it is an industry—it has to try to turn a profit when sales are minimal. And with so many books being published, libraries can’t keep up. The end result is high prices. I’m as guilty as the next academic at wishing economics would just go away and leave me alone. I want to believe in the pursuit of knowledge for knowledge’s sake. That’s not the way the world works, however. At least not the publishing world in a capitalistic context. The internet itself has become competition. Much of the information’s out there for free. So your academic book, when it comes out, will be priced out of your comfort range (been there, done that). It’s not that your publisher doesn’t believe in you, but that they have to try to turn a profit. All it takes to understand why is a bit of research.