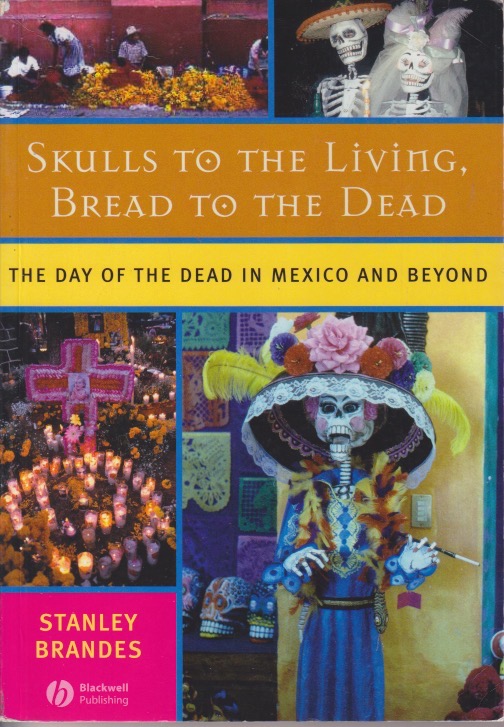

Probably nobody gives them much of a thought. ISBNs, that is. International Standard Book Numbers. An ISBN is a book’s unique identifier. And they cost money. I’m not sure how self-publishing works, but at some stage, whether it’s obvious or not, you have to pay for an ISBN if you want wide distribution. And since they cost money, most publishers don’t assign an ISBN until a contract is signed. If a deal falls through, hopefully they can recycle the ISBN and assign it to another book. The system only began in the 1960s and not all books printed their ISBNs. The thing about them is, the best way to find the book you’re looking for is by using the ISBN rather than the title. Titles can’t be copyrighted, and that’s why you see so many books with the same name. The ISBN won’t let you down.

My book, The Myth of Sleepy Hollow, now has an ISBN. I just found out yesterday. It’s 978-1-4766-9757-4, in case you’re curious. It won’t lead to anything on the web yet since I haven’t submitted the manuscript and work hasn’t begun on the title. It is, however, a step in that direction. In the past, when I’ve signed book contracts, I’ve always felt a little anxious until the ISBN is assigned. Is the publisher really sure about this? Once they assign an ISBN they’ve started to invest in your ideas. My book has existed in draft form for several months, but I’m going through it again, for the umpteenth time, to make it presentable to the world.

One of my jobs at Gorgias Press, my first full-time publishing gig, was to assign ISBNs. They had to buy blocks of them and they came in a printout in a large notebook. If a project with an ISBN didn’t materialize, some White-Out and a pen could save the company some money. It was all very hands-on. I imagine it’s gone electronic these days. The ISBN is a technical code, by the way. The 13-digit code, which is now common (it used to be ten), has a meaning. The schematic below explains that. The “group” section has to do with language and that’s followed by the publisher’s ID. Simple deduction (and dashes) tell me that 4766 is McFarland. That’s followed by the title identifier. I’m not a numbers person, however. Those of us drawn to the words part generally try to provide the inside content. And since it’s a weekend I’d better get to it. I have a submission deadline I’d like to meet. But I’m thinking about the ISBN.