One of the more interesting situations to emerge from Hurricane Sandy’s aftermath was the celebration of Halloween. I know that I’ve already lost some readers right there since Halloween is a disputed holiday. Often Halloween is maligned as “Satanic,” a claim that is absolutely untrue. It may have some paganism in its roots, but then, so do most religious events and ideas. Halloween is a Christianization of various folk customs, frequently Celtic in origin, on a night when the protective wall between the living and the dead was believed to be especially thin. As adults grew more sophisticated and scientifically informed, the holiday lingered as a children’s fun day with dress-up and pranking, both normal childhood ways of playing. This neutered holiday has proved to be commercially viable as well, now supporting September-October Halloween stores at a density of about a dozen per square mile. Its success is rivaled only by Christmas.

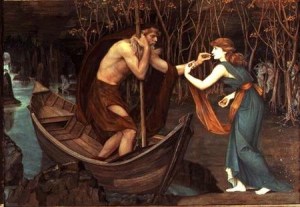

In light (or perhaps dark) of the devastation of Sandy, New Jersey Governor Chris Christie canceled Halloween. We heard the news on our battery-operated radio, sitting in the dark. While this was one of those rare times when I think Christie was motivated by the concern of both poor and rich, I did ponder the implications of a government canceling a holiday. All Hallows’ Eve is the night before All Saints’ Day. “Hallows” is simply another—less used but more evocative—word for “Saints.” While largely secular in its present guise, Halloween is a religious holiday. My mind went back to the doctrine of Two Swords that I learned about many years ago. Originating in the papal bull Unam Sanctum, very early in the fourteenth century, the doctrine teaches that in spiritual matters the church holds the sword while in temporal matters the state holds its own sword. Who has the right to cancel a holiday?

Of course, Chris Christie has his own ways of issuing bull, but his real concern was that conditions were too dangerous for trick-or-treating. Indeed they were. On a short walk, I saw power cables dangling like electrified cobwebs on just about every block, snaking along the ground. Branches were still falling from trees. Curfews (many still in effect) were widespread. Not a good night for masked strangers to show up at your door. But as in the case of the Grinch leaning out over Whoville after he’d stolen all the trappings, Halloween came, it came just the same. What we saw on Halloween was people helping one another. No tricks (for the most part, although among the first to recover were businesses who recorded new ads to broadcast on the radio before the wind even stopped blowing), just good natured mortals helping one another, protecting others from the grim reaper. To borrow a line from Charles Schultz, “That’s what Halloween’s all about, Charlie Brown.”