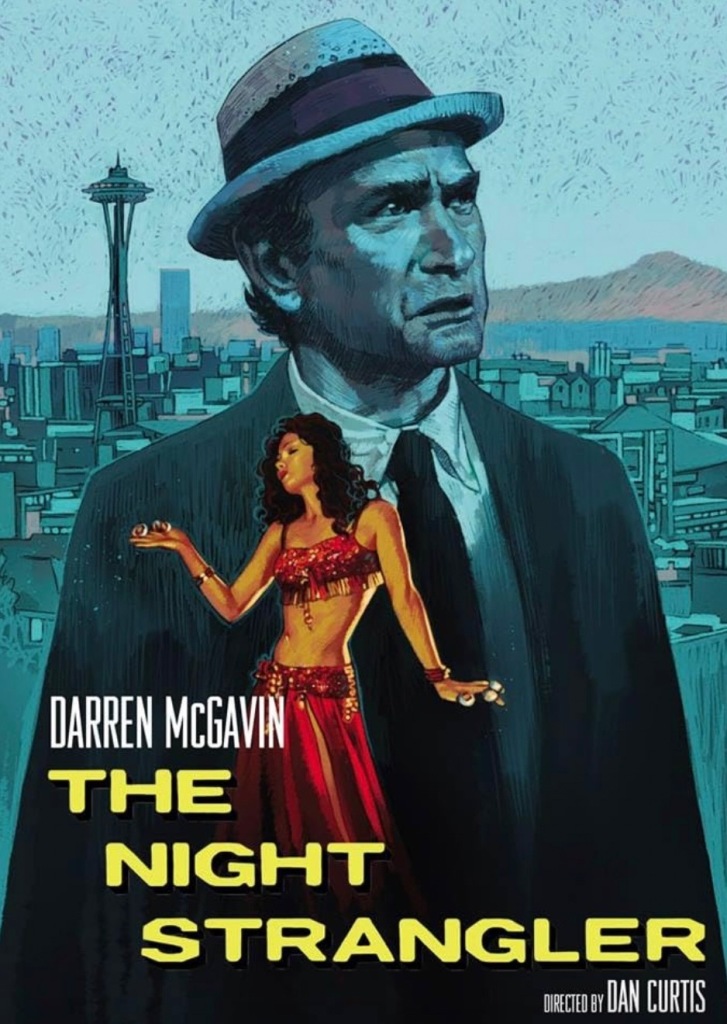

You had to’ve seen this coming. The Night Stalker introduced how Carl Kolchak, hard-nosed reporter, became a believer in the supernatural. This highly-rated television film led to a sequel, The Night Strangler, which appeared the following year. It also did well. Ditching a third script by Richard Matheson, ABC decided on a series, Kolchak: The Night Stalker. The subtitle was probably considered a necessary reminder that the movies had done very well. It also transferred the stalker epithet onto Kolchak. But I’m getting ahead of myself. The Night Strangler shifts the action to Seattle where an elixir-of-youth-drinking monster is murdering young women to keep himself alive. Once again the police and government officials cover up what’s really going on, for fear of losing tourist dollars. There is a bit of social commentary here.

This movie reminded me of an In Search of… episode on Comte de Saint Germain, who, as a child, I assumed was a Catholic saint. Saint Germain (just his assumed name) was an alchemist who claimed to be half a millennium old. He seems to be, guessing from the number of books that treat him as an actual saint, just as popular now as he was in the seventies. At least among a certain crowd. And it was in the seventies that this movie was released. Saint Germain’s enduring popularity all but assures no academic will touch him. No matter, we have Kolchak to fill in the details. And Richard Matheson was a smart man. The Night Strangler does have a few pacing problems, but it certainly is a film worth seeing, even though it exists in that shadowy world of telinema (the combined forms of television and cinema).

Kolchak succeeds by believing in where the facts point, although the conclusions are supernatural. In fact, watching The Night Stalker I couldn’t help but think of those who claim to have staked the Highgate Vampire. That’s some strong conviction. Indeed, the will to believe is more powerful than most people would like to admit. Our minds contribute to our reality, but we insist that minds = brains, despite our inability to define consciousness. That’s why I liked shows like In Search of… As a teenager I couldn’t get enough of it. I purchased all the accompanying Alan Landsburg books with my hard-earned summer income, skimping, as always, on the school clothes that I had to buy for myself. Funny, it seems that my mindset hasn’t changed that much since the days of my youth. Or maybe a sign of maturity is recognizing you were closer to the truth than you realized, back when you started the quest.