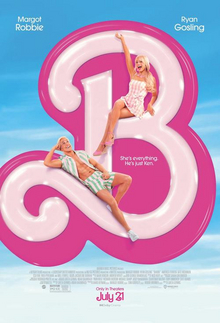

Of course I’d heard about it, but I hadn’t envisioned myself seeing it. My family, however, wanted to get in on the Barbie conversation and, I justified to myself, at least we’d be in air conditioning for a couple of hours. Besides, I now get “senior” rates at matinees! I knew very little of what to expect, and I was pleasantly surprised by what I found. In fact, I can’t remember the last time I saw a movie that was so full of social commentary. And I actually learned quite a bit. If you’re one of the maybe a dozen people who hasn’t seen it, the plot is more complex than you might think. And the writing is smart. And it’s funny. I was hooked from the opening parody of 2001: A Space Odyssey. The scene based on The Matrix made me realize that I was watching something unusual and important.

I’ll try to be careful with spoilers here, but basically, stereotypical Barbie experiences an existential crisis that leads her to the real world to find out what’s going on. Ken tags along, uninvited, and Barbie is distressed to find that the real world hasn’t been equalized between the genders the way that she was intended to help it become. While in the real world Ken gets a taste of patriarchy and decides to take it back to Barbie Land. When Barbie returns she finds her once perfect world upside down. But that’s not quite right. She comes to realize that the world run by women wasn’t exactly perfect because men and women need to cooperate and share some responsibility.

There’s a lot more to it than that, of course. How we’ve gone for centuries maintaining male dominance (might makes right philosophy), even while claiming to be “enlightened” is a mystery. Gender inequality is one of the biggest social concerns we experience. Almost nowhere in the world are societies truly equal and Barbie offers a funny, yet poignant way of thinking about that. I wouldn’t bother writing about it if the message wasn’t important. The movie isn’t a feminist screed. Nor is it simplistic drivel. It’s a surprisingly sophisticated consideration of a society out of balance. I’ve been in favor of equal treatment of women for as long as I’ve been conscious of the difference. Raised by a capable single mother, I noticed in my formative years that she was doing what two-parent families did, with less than half the resources. While Barbie won’t solve all our social ills, it is getting the conversation going. From my point of view, it’s about time.