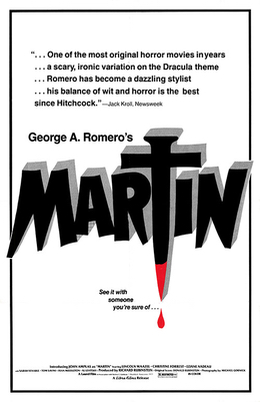

I’d heard that Martin was a depressing movie but I felt I should watch a Romero film that wasn’t about zombies. I’d read bits and snatches of what happens, but I didn’t know the storyline in total. Now that I’ve seen it, I’m still not sure what to make of it. Martin is a young man who believes himself to be a vampire. He does drink blood, murdering his victims, but there are no fangs, no “magic stuff” as Martin himself calls it. It seems pretty clear that he’s mentally unbalanced, but he’s brought into his older cousin’s house in Braddock, Pennsylvania. Cuda, his cousin, believes him to be a vampire, calling him “Nosferatu.” He has protected his house with garlic and crucifixes, but Martin demonstrates that such things (magic stuff) doesn’t work.

Daylight and eating regular food don’t bother him. His cousin gives him a job at the grocery store he runs, while constantly warning Martin about looking for victims in Braddock. Shy around women, he only has sex with his victims, after he has drugged them. (This is a pretty violent movie, and the tone is downbeat throughout.) Since he has no friends, he calls into a radio talk show to discuss the problems of being a vampire, and people love listening to him. Meanwhile, Cuda arranges for an exorcism on Martin, which doesn’t work. There are black-and-white sequences that aren’t really explained—either as fantasies or as past memories for a real vampire. After his cousin becomes too suspicious, he stakes Martin to death and buries him in his back yard.

There are many unanswered questions about this movie. If Martin is a vampire just about everything in traditions about them is wrong, apart from needing to drink human blood. When Martin begins an affair with a troubled housewife, his bloodlust lessens, but he still gets “shaky” and has to find victims. For those of us who tend to find ambiguity both beguiling and confusing, this is a vexing movie. It makes you wonder what a vampire really is, and, as with most of Romero’s work, there’s a fair bit of social commentary—intentional or not. Life itself has its fair share, perhaps more than its fair share, of ambiguity. The only real certainty that Martin gives is that his victims die and he himself dies in the end. Is his cousin correct? Is Martin himself correct? He may be mentally ill, but society is too. And the working-class people of Braddock should know who the real vampires are.