Those who know me know that I treat my workdays like clockwork. I leave the apartment every day, catch the same bus, and leave work at the end of the day, all according to schedule. Traffic is a variable, of course. Yesterday as I came out of the Port Authority Bus Terminal at 7:15, blunted with my reading on the bus, I noted we were a bit late for my liking. I got to work before 7:30, though, and was interrupted by a message from my brother, asking if I had made it out of the Port Authority okay. I was a bit confused—weather delays do happen, but what could have made today any different than any other Monday? It was then I learned about the bombing. It happened five minutes after I left.

Now, I’m not trying to over-dramatize this. I was above ground and the bomber was below. I didn’t even hear it go off, although there were a lot of sirens on my way to work. The only serious injury was to the bomber himself. What really got to me, when the idea had time to settle in, was how close I’d been. So were thousands of others at the time. Over the summer I went to Penn Station just after what had been assumed to be a terrorist attack. Jackets and personal effects lay scattered on the floor. People had dropped things and ran. In that case it had been an innocent tazing of an unruly passenger that had set off the panic. I’m not a fan of fear on the commute. I don’t think, however, that we should give in to the rhetoric that our government will surely use to describe all this.

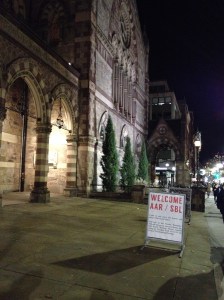

Millions of people live and work in New York City. Such things as these disrupt the flow of our daily lives, but we can’t let the agenda of fear control this narrative. I felt a tinge of it when I headed back to the Port Authority at the end of the day. Police barricades were still up on 8th Avenue. Reporters with cameras were at the scene. A potential killer had been here just hours before. This is New York. Without the overlay of fear, this was simply business as normal. Any city of millions will harbor potential killers. If terror controls the narrative, it has won. If politicians use this fear to win elections, the terrorists win them too. I’m doing what we must do to defeat the fear. I’m just getting back on the bus.