One of my most frequent imaginary dalliances is wondering what I would have done with my life if I hadn’t been raised religious. Like many young boys I found “exciting” jobs enticing—soldier, firefighter, explorer—but scientist also loomed large in my imaginary horizon. By the time I was a teen I was firmly ensconced in books. My upbringing meant that many of these books were religious in nature, and my concern with ultimate consequences meant religion was the only possible career track to make any sense. It certainly never made dollars. As someone who professionally looks backwards, I’ve found myself wondering if I shouldn’t have focused on English rather than Hebrew and Ugaritic as a career. After all, the Bible has been available in English for centuries now. Besides that, the canon is larger—from Beowulf to Bible and beyond. Reading is, after all, fundamental.

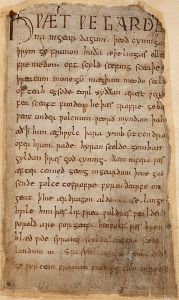

I only discovered BookRiot recently, and that through the mediation of my wife. For the writer of a blog I really don’t spend that much time online outside of work. I like real books, and being outdoors. Too much time staring at a screen brings me down. Nevertheless, BookRiot has stories that cause me to question my career choices from time to time. For instance, I have never knowingly heard of The Exeter Book. Dating to the tenth century, this medieval manuscript is among the earliest of English writings. Showing the interests of the monk who likely inscribed it, it has religiously themed material and riddles. As E. H. Kern’s post on BookRiot points out, The Exeter Book has inspired many later writers and has, through them, made its way into mainstream popular culture. Not bad for a book that I suspect many, like myself, have never heard of.

Old English has the same kind of draw as other ancient languages. Not nearly as dusty as ancient Semitic tongues, it contains the roots to the form of expression I find most familiar. I love looking back at the Old English of Beowulf and spotting the points where my native language has remained relatively unchanged over the centuries. Modern English even begrudgingly owes a considerable debt to the Bible of King James. Our language is our spiritual heritage. We have trouble expressing our deepest thoughts without it. Perhaps had BookRiot existed when I was young, I might have made a rather more informed decision about the direction of my career. Or, then again, religion might have found me nevertheless. From some things there is just no hiding.