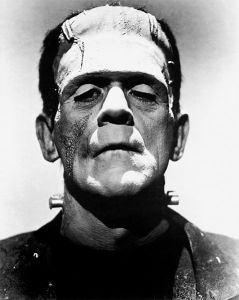

Two centuries can make an enormous difference. Just two-hundred years ago Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo was merely one year in the past. North America and parts of Europe were experiencing “the year without a summer.” Perhaps due to that cool and rainy summer, when Mary Godwin and Percy Bysshe Shelley called on their friend Lord Byron, their thoughts turned to ghosts. According to the legend, together with Byron’s personal physician John Polidori, the friends spent a night writing scary stories. Polidori, although not widely remembered today, invented the vampire that would, in Bram Stoker’s hands, become the aristocratic Dracula, and eventually, with Anne Rice’s influence, Lestat, Louis, and Armand. Mary Godwin, soon to be Shelley, gave birth to perhaps the most successful of new monsters ever created—that of Victor Frankenstein’s construction. Many have claimed the monster’s pedigree to have been that of the golem, but Shelley’s creativity went beyond this forebear into the sympathetic misfit who, like all of us, never asked to be born. The two centuries since that summer have been haunted.

Quite apart from the monster tale, Frankenstein is also about building that which we, in our hubris, can’t understand. Progress without forethought, as Epimetheus could never learn, housed immediate and very real dangers. The two centuries since Frankenstein have proven Mary Shelley a prophet. An early supporter of women’s equality, she profited from her novel, but never managed to thrive. Just six years later her famous future husband would die tragically in the Romantic genre of a shipwreck. Even with important friends, Mary found it difficult to capitalize on her success. The monster was real enough.

We’ve become accustomed to making things we can’t control. When’s the last time you were able to fix a car broken down by the road, apart from the occasional flat tire? Can you really stop your job from becoming completely different from what you signed up to do? What about when that bully wanders from the playground into the political field? Once you’ve figured out how to split an atom, you never forget. It may have been Napoleon still recently in the news, or the fact that 1816 failed to warm up like it was expected after the solstice. Perhaps it was the fact that Mary Godwin was a liberated woman in a world still utterly determined by men. We can’t know her intimate and ultimate reasons for creating a monster, but we do know that once the monster is unleashed we can never bind it again.