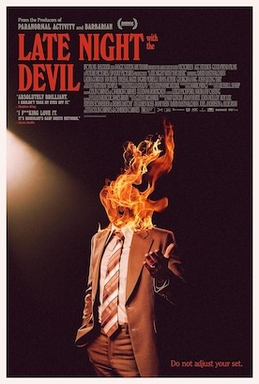

If you lived through the seventies, Late Night with the Devil will take you back a bit. It’s one of the more creative possession movies I’ve seen, but what really makes it stand out is the insider winks plentifully on offer. Jack Delroy is a late-night variety show host wanting to top Carson. His ratings have been up and down, and he decides to make his 1977 Halloween episode his ticket back into the game. His guests that night include a psychic, a James Randi-like debunker, and a parapsychologist and her demonically possessed charge, Lilly. A character resembling Anton LaVey, Lilly’s father, had raised her to be a child sacrifice to the demon Abraxas. The broadcast even mentions Ed and Lorraine Warren, as well as The Exorcist. Someone knows what the paranormal scene was like in the seventies.

The psychic has authentic contact with what he believes is Delroy’s deceased wife and while the debunker, well, debunks him, the psychic nevertheless dies after a mysterious attack. Delroy insists that the parapsychologist summon Lilly’s demon, while on stage. The debunker claims that what the audience saw was a case of group hypnosis, but the demon finally attacks, killing everyone but Delroy and Lilly. Toward the end the layers of claimed deception become so deep that it’s difficult to know, at first, how to interpret the ending. Or whether you are supposed to “believe” the climatic demonic attack, of if you’re supposed to conclude that it was part of the mass hypnosis. What is certain is that religion is front and center in this horror, but the demon ensures that in any case.

The taped pieces between segments of the show make it clear that this is all about ratings. Indeed, Delroy sacrificed his wife’s health and life to try to break into the lead. The real demon here is capitalism. The desire to be on top has outweighed every other and hints are given throughout that Delroy isn’t as innocent as he pretends to be. Still, the main thing is that the movie gets the paranormal seventies in America just about right. The disturbing implication is that people are suggestible to the point of not being able to distinguish reality from manipulation. That pall hangs over the entire movie plot as well as the ending. This kind of meta critique isn’t intended to detract from what is really quite a good horror movie. It is believable in the context of the world it devises, and that world includes demons.