One of the most terrible stories in the Bible is the slaying of the firstborn of Egypt. Of course, depending on your point of view, this was either a necessary evil or an act of wanton cruelty by a deity with anger issues. Still, it ends with a bunch of dead children. Then, as if that weren’t enough, a horrible reprisal comes at the birth of the child of the main character, with Herod slaughtering the innocents in Israel. And let’s not forget the very source of Kierkegaardian angst, the knife poised above a bound Isaac by his completely believing father. More recent, less literary examples could add poignancy and reduce the distance: Columbine, Newtown, Virginia Tech—the murder of children is beyond the farthest reaches of perversion into a realm that no longer classifies as human. I think the Bible might agree with me there. So it was with some trepidation that I read Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games, at the urging of my daughter.

One of the most terrible stories in the Bible is the slaying of the firstborn of Egypt. Of course, depending on your point of view, this was either a necessary evil or an act of wanton cruelty by a deity with anger issues. Still, it ends with a bunch of dead children. Then, as if that weren’t enough, a horrible reprisal comes at the birth of the child of the main character, with Herod slaughtering the innocents in Israel. And let’s not forget the very source of Kierkegaardian angst, the knife poised above a bound Isaac by his completely believing father. More recent, less literary examples could add poignancy and reduce the distance: Columbine, Newtown, Virginia Tech—the murder of children is beyond the farthest reaches of perversion into a realm that no longer classifies as human. I think the Bible might agree with me there. So it was with some trepidation that I read Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games, at the urging of my daughter.

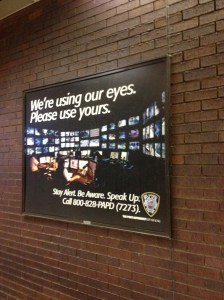

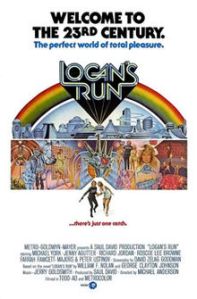

Although written for a young adult readership, The Hunger Games is a classic dystopia with a dark future and repressive government mandating the killing of twenty-three children every year, just to make a point. Deftly combining teenage angst with the bleakness that just about any future-based novel seems to hold, Collins spins a sad but engrossing tail. Dystopias have grown in popularity since some of the earlier, Cold War exemplars such as 1984 and Fahrenheit 451. The number of dystopian novels grows every year. I suppose if I were an elected official I might cast a worried eye towards the increasing number of exposés of a society where consumers read so many books of the future gone awry. I know many intelligent, sober people who seriously wonder if we’ve already shifted onto that track. Tomorrow is only an extension of today.

Dystopias are among the most biblical of literary genres. The Bible itself is a bit of a dystopia. Consider the framing of a perfect world ending up with the original apocalyptic tale, the Apocalypse, or Revelation. It only ends well for 144,000. In-between there are pages and pages, chapters and chapters of oppression, violence, and suffering. Paradise gone bad. That’s the essence of the dystopia. Although Collins doesn’t make any overt biblical or religious references in The Hunger Games, the very genre she chose can’t escape the biblical bounds laid out for it. And besides, long before the year both Collins and I were born, the Bible had already set its vision for our society. And that vision, to our everlasting trembling, includes the massacre of innocents.