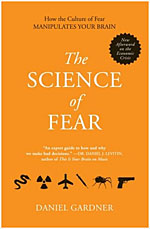

“The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom,” so the books of Psalms and Proverbs agree. It must be true. Religion and fear walk happily along hand-in-hand. Some have suggested that religion began as a human response to fear. So this week I felt a little conflicted as I read Daniel Gardner’s The Science of Fear: How the Culture of Fear Manipulates Your Brain. The book had been recommended to me by one of my brothers. As a child fear defined me—it seemed that in a world where God was meant to be feared (for I was a literalist) that fear was the basic operating system for life itself. Gardner’s book is a fascinating exposé of the culture of fear. Gardner doesn’t really suggest that fear should be eliminated, but he does show how many of those in power manipulate fear into a faulty perception of risk management, for their own advantage. Beginning with 9/11 he demonstrates how the irrational responses of people to the tragedy led to even more deaths that quickly became buried in the white noise of everyday society. Comparing Bush’s response to FDR’s “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” Gardner demonstrates that the United States emerged from the depression and Second World War weary but confident and strong. After Bush’s two terms, the country is cowering and weaker. Why? The Bush administration heavily mongered fear.

“The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom,” so the books of Psalms and Proverbs agree. It must be true. Religion and fear walk happily along hand-in-hand. Some have suggested that religion began as a human response to fear. So this week I felt a little conflicted as I read Daniel Gardner’s The Science of Fear: How the Culture of Fear Manipulates Your Brain. The book had been recommended to me by one of my brothers. As a child fear defined me—it seemed that in a world where God was meant to be feared (for I was a literalist) that fear was the basic operating system for life itself. Gardner’s book is a fascinating exposé of the culture of fear. Gardner doesn’t really suggest that fear should be eliminated, but he does show how many of those in power manipulate fear into a faulty perception of risk management, for their own advantage. Beginning with 9/11 he demonstrates how the irrational responses of people to the tragedy led to even more deaths that quickly became buried in the white noise of everyday society. Comparing Bush’s response to FDR’s “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” Gardner demonstrates that the United States emerged from the depression and Second World War weary but confident and strong. After Bush’s two terms, the country is cowering and weaker. Why? The Bush administration heavily mongered fear.

Funnily enough, the release from fear comes from two main sources: statistics and psychology. Statistics reveal the true odds of common fears—these can be inflated so as to create an atmosphere of threat. People, as herd animals, will gladly give more power to the alpha male when serious treat is perceived (don’t kid yourself, politicians have long known this). Psychology enters the scenario because people think with both reason and emotion. Our immediate, visceral response (the “gut reaction”) is instantaneous and powerful, developed from millennia of evolution. It is, however, irrational. Reasoned responses, often better for us, take longer and people do not like to force themselves to think hard. We have a whole educational system to prove that. Faced with hard thinking or quick solving, which do you prefer? Be honest now!

Ultimately The Science of Fear is an optimistic book. Being made aware of the problem is half the struggle. Garden-variety fear is fine. Systemic fear paralyzes. Religion is often defined as one of the building blocks of culture. Instead of offering release from fear, religions frequently add their own ingredients for recipes of even greater fear. The concept of Hell is a great example: think of the worse thing you possibly can. Multiply it by several orders of magnitude. Repeat. And repeat. You’re still not even close to how bad Hell is. There’s your motivation right there. Place that religion in the midst of a society rich with natural resources and led by schemers who know that xenophobia increases power, and voila! Paradise on earth for some, a life of fear for the rest. Manipulation characterizes both the evolution of religions and societies. Gardner doesn’t directly address the religious side, but that’s the beauty of reason: he doesn’t have to. The cycle can be broken; think of Mark Twain’s words I’ve selected as a title. Think hard.