It’s hard not to feel sorry for survivors. In a hostile world, the ability to resist the entropy lapping at your toes is a feat that inspires admiration. Although independent bookstores are making a comeback, there aren’t many around. An evening spent at Barnes and Noble, if allocated well, can evoke some sympathy even for a dying giant. While my wife had an appointment next door, I spent a good while in the fiction section—really the only part of our local B&N that is well stocked. My time among books, excessive to some, is my solace. It’s not a bad vice to have. Seeing others out shopping for books also delivers a message of hope to a world disinclined to read.

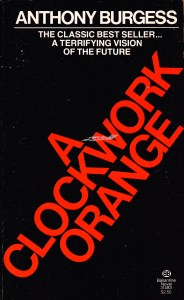

In the B section I saw an edition of A Clockwork Orange. If you read my post on Anthony Burgess’s book in the last few weeks, you’ll know that the American edition has always lacked the last chapter. I wondered if maybe, just perhaps, if this edition might contain the missing ending. It has been several decades since the original embargo. I picked it up and, indeed, the last chapter was intact. I stood in the aisle and read it. Say what you will about Barnes and Noble, but nobody thinks this kind of behavior odd. Once again I was transferred back to Alex and the world of his droogs, only to discover that the ending was something like I had anticipated. If you’ve read the standard American edition you know that it ends abruptly. Writers know how to draw a story to a close. Herewith I offer a spoiler alert.

Alex, now 18, has a new band of droogs. They sound quite a bit like his previous gang. Then he notices he doesn’t feel like the old ultra-violence one night. He goes to a coffee shop where he finds Pete, his old gang-mate, now married and holding a respectable job. He realizes with a kind of horror that having a child and wife appeals to him. He’s growing up. Critics often said Burgess was a moralist with Christian sensibilities. The original ending to A Clockwork Orange might suggest that’s true. Alex may be converted, but he’s unrepentant. Indeed, as he thinks of being a father he envisions his son being just like he was, and the cycle of violence and reform spinning on and on into the future. Shortly after I closed the cover, my wife met me in the store. I was amazed at how 15 or 20 minutes immersed in reading had shifted the mental world I inhabited. New information had changed me. This is the power of books, even when they’re found in Barnes and Noble.