Even in days of secular education—I am a product of public education throughout my childhood—Jonathan Edwards is a name that still retains recognition among many Americans. Perhaps best remembered for his sermon, “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” Edwards thrived at a time when being a clergyman was a recognized path to success in this world as well as the next. Not that all ministers became famous, of course, but those with the inclination had access to books and time to study. They could write books and influence public policy. Indeed, Edwards was part of the “Great Awakening” that spread throughout the young United States, before its independence. George Whitefield had brought a showman’s sensibility to preaching, and people gathered to listen to roving reverends who brought their wisdom to new locations. In fact, revivals continue to this day—I had attended a few as a child—and they are largely responsible for the denominational map of American Protestantism even today. The “Second Great Awakening” brought Methodists and Baptists into the mainstream to stay.

The first major revivals, however, were fueled by a Calvinistic intensity. Having spent many of my educational years in schools established or supported by Presbyterians, I know their theology well. Judgment is important in the Reformed tradition. Indeed, without the element of threat, the heat is stolen from much of revivalism. Edwards’ sermon encapsulates so well the vital element of a theology that preached total depravity, unconditional election, limited atonement, irresistible grace, and perseverance of the saints. In other words, unless God has already selected you, you’re out of options. As Presbyterian teachers were eager to state, you should still try to live as if you were saved (“elect”), even if you were going to Hell because of, well, you know, an angry God. Campus rules at Grove City embodied that ethic in a real-time way.

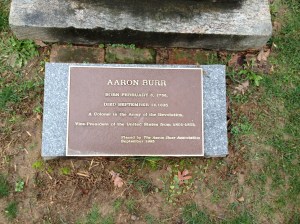

Jonathan Edwards went on to become president of Princeton University (the College of New Jersey, at that time). He died at about my age, having been inoculated for small pox—he was a believer in science—to demonstrate the value of the practice to students. He contracted the disease and died merely weeks later. Ironically, Edwards felt he was past his prime and had to be persuaded to take an academic job—somewhat of an extreme rarity today—and largely because his son-in-law, Aaron Burr, Sr., had recently died as the incumbent. Today, starting on the path to ministry is often a fast-track to job insecurity, popular derision, and poor earnings. For all that, it is difficult to be accepted in the ordination track without jumping through many hoops. So Jonathan Edwards came to rest in Princeton, New Jersey, as a famous, published, and highly respected man. A more different world then his in such a short time in the same location, is hard to imagine.