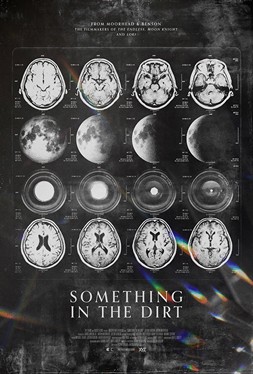

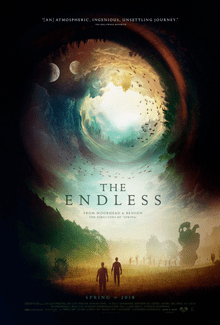

A friend suggested I might like Justin Benson and Aaron Moorhead films. An unusually intellectual type of horror, these movies challenge perceptions of reality and are tied together with one or two thematic elements. Something in the Dirt is their most recent offering and as far as existential horror goes, it’s a winner. The storyline, as with their other films, plays with alternative realities bleeding over into what we think of as everyday life. There’s a lot going on in this one that will keep you guessing until the end, and even after that. Levi, a ne’er-do-well, awakes in his cheap apartment in LA and meets his neighbor, John, just outside. Even this initial meeting has a sense of the surreal about it, but the two strike up a conversation, each trying to weigh the other’s truthfulness.

Levi’s apartment begins to show elements of paranormal happenings. Neither he nor John have professional careers, so they figure they can use their off times to make a documentary about the phenomena to sell to maybe Netflix, setting them for life. They each start coming up with theories about what is happening from ghosts to extraterrestrials to Pythagoreans building Los Angeles on an occult geometric pattern. Ultimately they seem to settle on two basic forces of nature: electromagnetism and gravity. Both are distorted in this apartment. Meanwhile, each learns that the other isn’t quite what he seems to be. Levi has a history of arrests that he downplays. John is the member of an evangelical, apocalyptic group, but he’s also gay and claims to have made a ton of money that he donated to the church. (Religion and horror, folks!) Neither really trusts the other but synchronicities keep occurring, preventing either one from just ending the project.

They bring in occasional experts who have varying degrees of skepticism regarding whether the two are faking what they capture on camera. After all, they include reenactments along with their actual footage. I won’t spoil the ending here, but it is pretty much what a seasoned viewer of Benson and Moorhead might appreciate. These movies are so unusual and so full of hard thinking that it seems odd that they aren’t discussed more often. If I understand correctly, there is only one remaining film where they appear as writer, director, producer, editor, and director of photography that I haven’t seen. They are the kinds of movies that if you binge on you’ll either end up enrolling in a graduate program in philosophy or spending the rest of the day blowing dandelion seeds into the wind. Or maybe there’s something in all this.