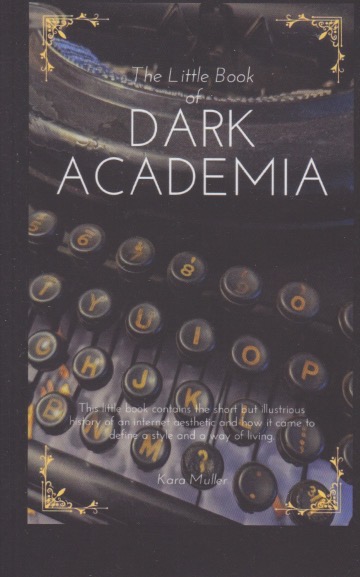

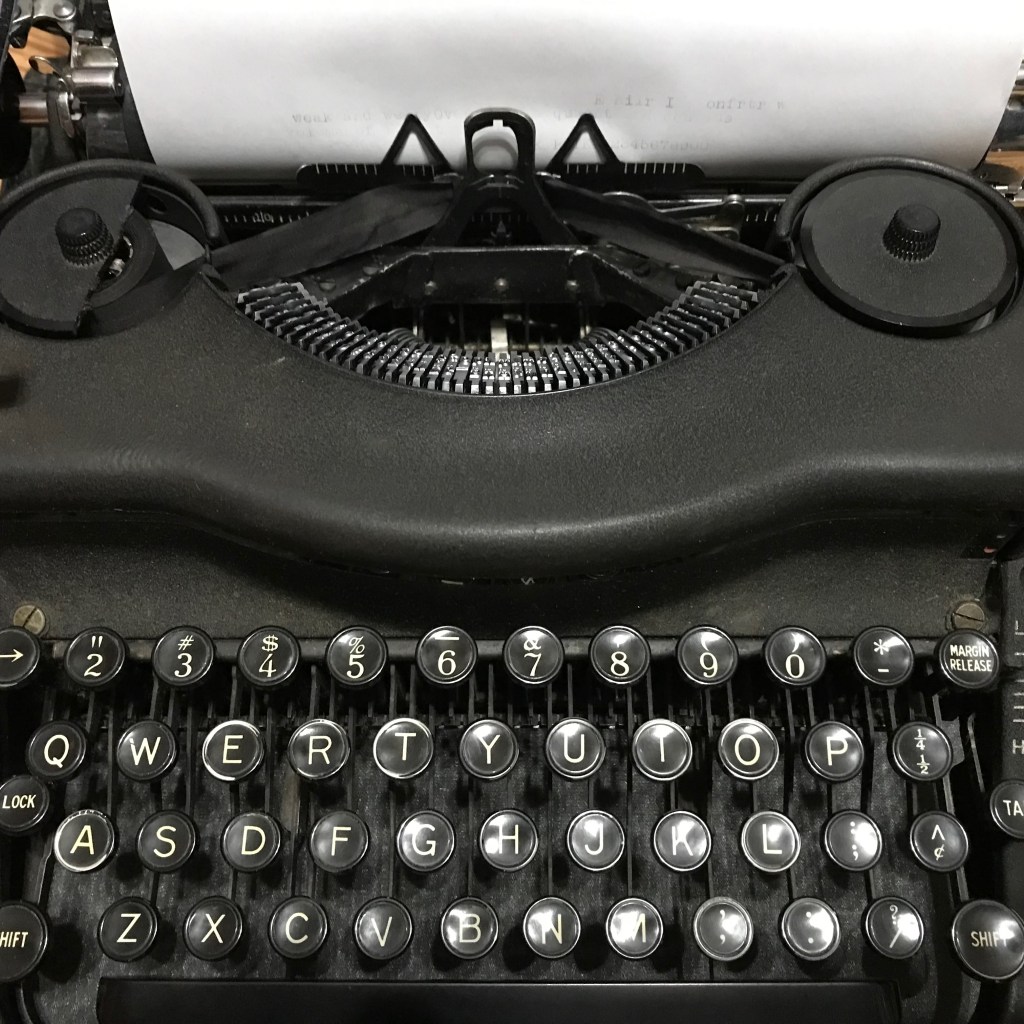

Since I’ve discovered that I live in dark academia, I’ve grown curious. Kara Muller has put together The Little Book of Dark Academia as a kind of first step in the discussion. I have learned that some academic articles on dark academia are starting to appear, but this is pitched more toward those who maybe need some tips on how to get started. By the way, this is a full-color, heavily illustrated book. In practical terms, that means it doesn’t take too long to read it. It’s also self-published, so less expensive than many books, but without editorial shaping. It begins with history and definitions. The term came into use in 2015 but the concept had been around much longer than that. Sometimes a label is necessary to bring together thought on something that’s been floating around for a while. As Muller points out, it tends to revolve around books.

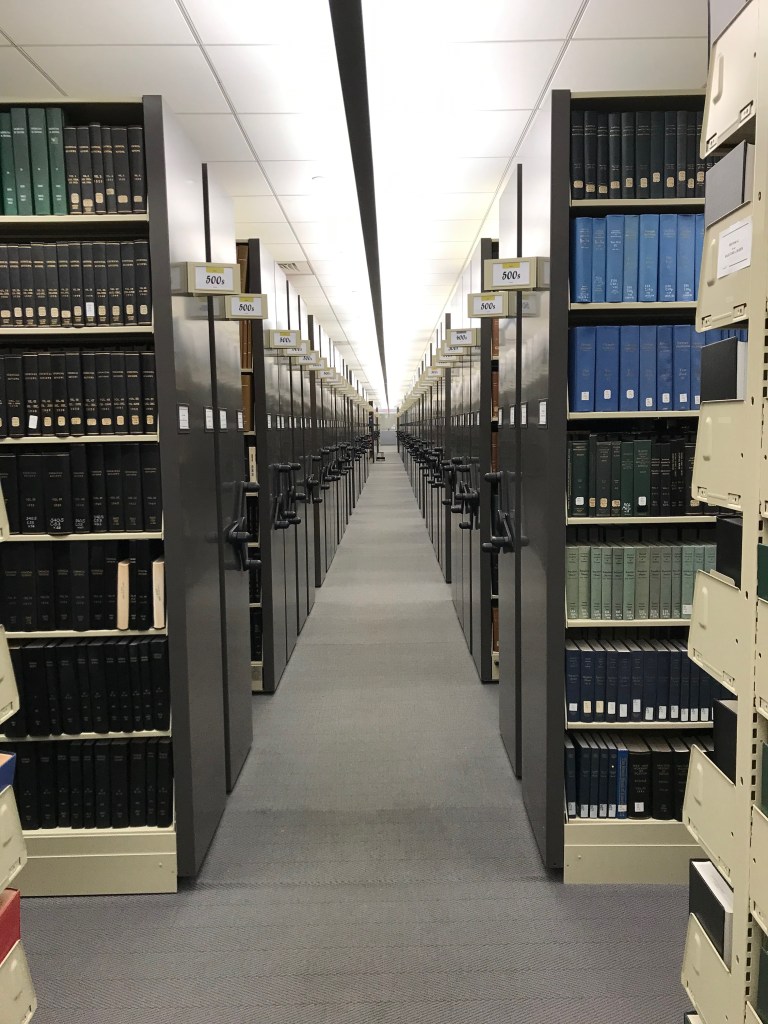

My imagination isn’t so constrained as to believe that ebooks have no place in dark academia; they have their own special kind of darkness. Still, the setting for these stories often takes place in real life, in studies and libraries full of books. This is not a Star Wars paperless universe. Muller gives a list of acclaimed dark academia titles with a brief paragraph or two about them. In other words, a reading list. And also a movie viewing list. She also includes some television series that fit the aesthetic. If you’re in the mood for dark academia, you’ll find plenty of places to indulge your hunger here. The lists aren’t comprehensive, of course. A bit of searching online indicates that many such lists exist, not all of them in full agreement.

Muller then presents a section on style and design. Dark academia is, in many ways, like cosplay. There’s a look and feel to it that can be emulated. And I can’t help but say it’s backward looking. A longing for classical education, the way that it used to be. To me, this seems to be behind much of the current fascination with it. This lifestyle is rapidly disappearing. Even professors are now using AI instead of getting their hands dirty in the library. And publishing online rather than in print form. Showing up to class in tee-shirts and jeans. Some of us, and I count myself in their midst, miss the feel of armloads of books and professors that wore tweed and could read arcane languages. And nobody was trying to cut their funds because, well, the world was smarter then. And everyone knew education was important.