It’s a reciprocal relationship. Ideally a symbiosis. The publisher has a reach, and know-how, that an author lacks. An author provides content the publisher needs. Yet publishing is a business in a capitalistic world and has to (unless subsidized) turn a profit. As an author who works in publishing I’m skewered on the horns of this dilemma. It’s heartbreaking to see the lengths some authors go to only to find out their book is priced the same as a week’s worth of groceries. Or three tanks full of gas. Who buys a $100 book? Libraries. Well, some libraries. Occasionally a publisher will run sales, if you order direct, but by then interest in your book (which may be timely) has passed on. You become just another name on the shelf in the Library of Congress.

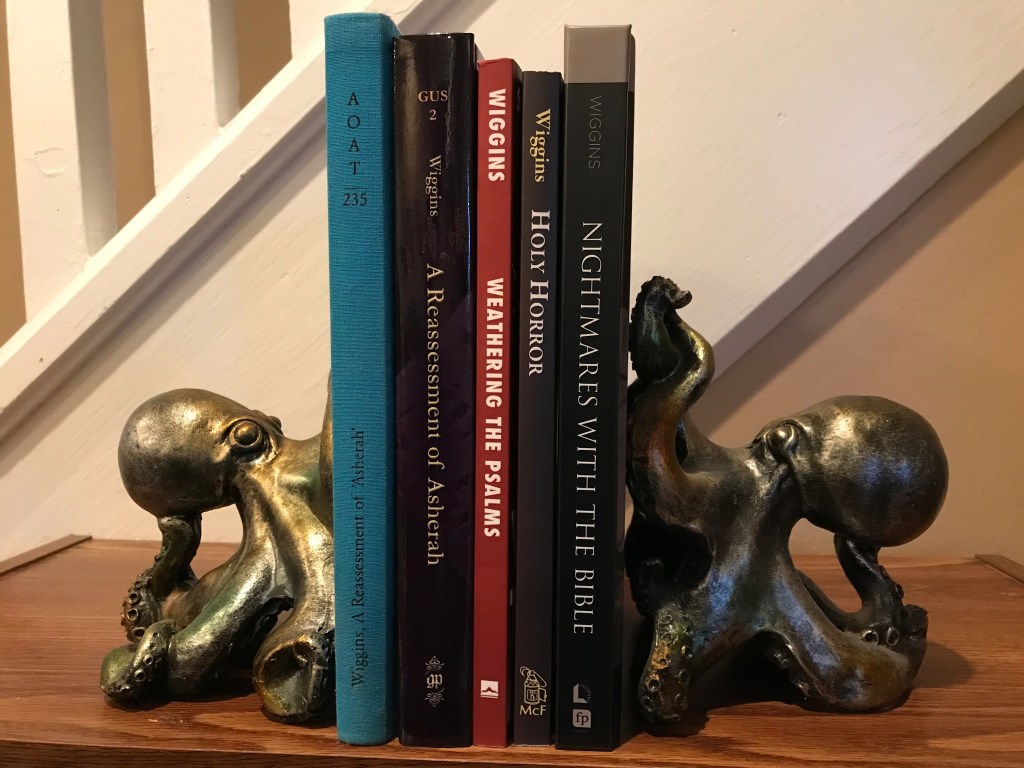

I’m looking for a publisher for my sixth book. This has to be someone who understands that even $45 is beyond the reach of most intelligent readers. “What the market will bear” feels like the death sentence to the years of your life you’ve put into writing the thing. A friend once asked me, “Why do you do it?” For authors the real question is “How can you not do it?” The need for the validation through publication runs very deeply in some people. More deeply than our national love for Taylor Swift. It has to do with meaning. Purpose. A sense of what we’re put on earth to do.

The standard “wisdom,” and practice, is to publish in hardcover, priced for the library market, and if it sells well at $100, perhaps offer a paperback. Hopefully priced lower than $45, but don’t hold your breath. “What the market will bear,” should be your mantra. It’s a wonder that civilized people ever got educated. I grew up on cheap books from Goodwill, which is all I could afford. College, on borrowed money, taught me the price of reading seriously. It was a lesson I never forgot. I’d begun my faltering steps to writing books while in high school. I started writing short stories even earlier than that. It has been a life of writing. Even series books, I’ve come to see, are too easily exploited in this way. My shortest book is priced at $40. At least I know that I’ve written some collectors’ items. Take heart, my fellow writers trying to emerge from academe. There are other ways of being in the world. And some of them may even be symbiotic.