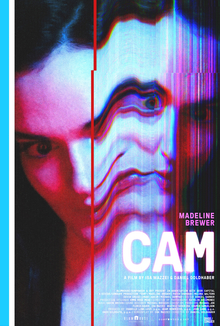

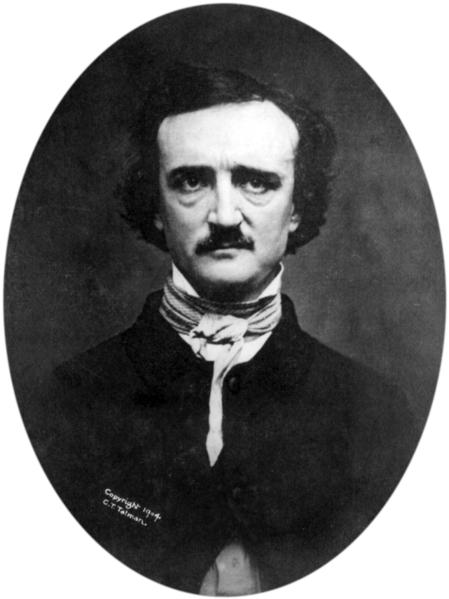

Techno-horror is an example of how horror meets us where we are. When I work on writing fiction, I often reflect how our constant life online has really changed human beings and has given us new things to be afraid of. I posted some time ago about Unfriended, which is about an online stalker able to kill people IRL (in real life). In that spirit I decided to brave CAM, which is based on an internet culture of which I knew nothing. You see, despite producing online content that few consume, I don’t spend much time online. I read and write, and the reading part is almost always done with physical books. As a result, I don’t know what goes on online. Much more than I ever even imagine, I’m sure.

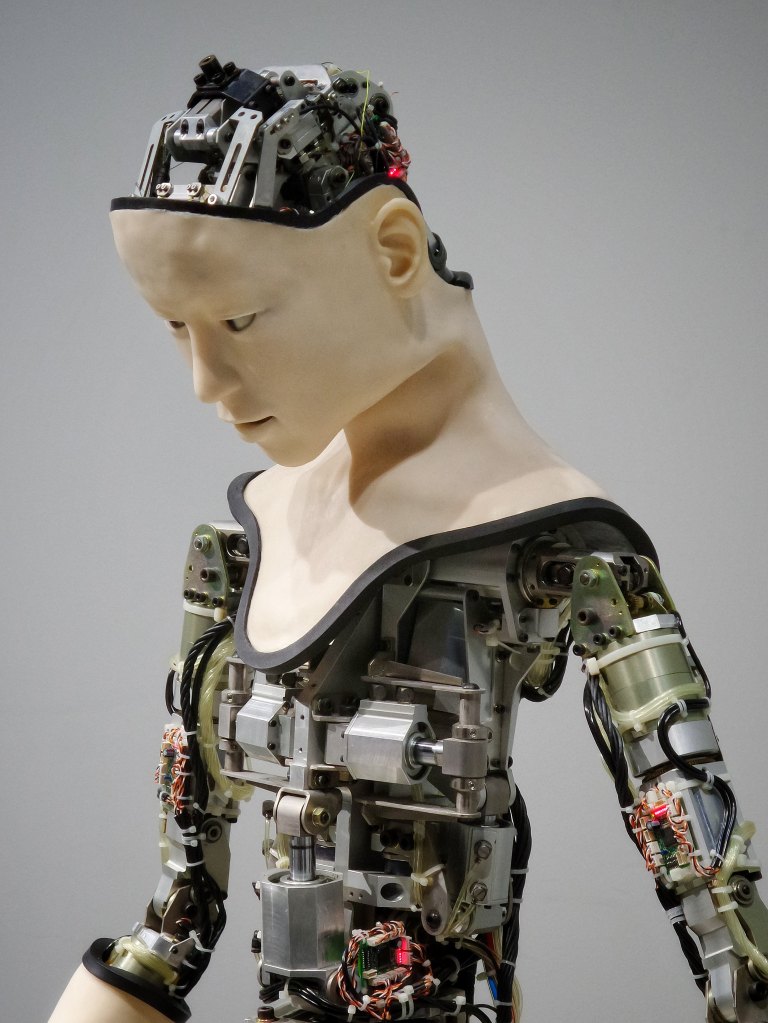

CAM is about a camgirl. I didn’t even know what that was, but I have to say this film gives you a pretty good idea and it’s definitely NSFW. Although, having said that, camgirl is, apparently, a real job. There is a lot of nudity in the movie, in service of the story, and herein hangs the tale. Camgirls can make a living by getting tips in chatrooms for interacting, virtually, with viewers and acting out their sexual fantasies. Now, I’ve never been in a chatroom—I barely spend any time on social media—so this culture was completely unfamiliar to me. Lola_Lola is a camgirl who wants to get into the top fifty performers on the platform she uses. Then something goes wrong. Someone hacks her account, getting all her money, and performing acts that Lola_Lola never does. What makes this even worse is that the hacker is apparently AI, which has created a doppelgänger of her. AI is the monster.

I know from hearing various experts at work that deep fakes such as this can really take place. We would have a very difficult, if not impossible, time telling a virtual person from a real one, online. People who post videos online can be copied and imitated by AI with frightening verisimilitude. What makes CAM so scary in this regard is that it was released in 2018 and now, seven years later such things are, I suspect, potentially real. Techno-horror explores what makes us afraid in this virtual world we’ve created for ourselves. In the old fashioned world sex workers often faced (and do face) dangers from clients who take their fantasies too far. And, as the movie portrays, the police seldom take such complaints seriously. The truly frightening aspect is there would be little that the physical police could do in the case of cyber-crime. Techno-horror is some of the scariest stuff out there, IMHO.