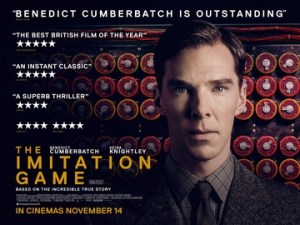

The enigma machine held an almost impossible complexity for generating codes. It gave the Nazis a great advantage during World War II since it was beyond the ability of cryptographers to decipher it. It was against this background that Alan Turing developed what would come to be recognized today as the computer. A brilliant mathematician, Turing himself was an enigma, in part because he was a homosexual—and in Britain at the time acting on this was a crime. Turing famously committed suicide just at the start of a brilliant career, probably because of his conviction of this “crime.” Those of you who’ve seen The Imitation Game will recognize the plot of the movie, and most people who read about technology will recognize that the story is largely factual. We like to think we’ve progressed since the days when one’s sexual orientation was considered a crime, but the enigma of the election has proven indecipherable once again.

As we begin to realize just what the price will be to have an avowed bigot in the highest office in the land, it may be helpful to decode things a bit. I, for one, have to admit that having a few days off from work and avoiding the news as much as possible, has been restorative. Watching movies, spending hours at a time writing, and actually seeing family when we’re all awake have been wonderful. Now it’s time to face the cold realities of 2017 with early morning bus rides and a looming intolerance on the horizon.

I have to admit that my mind doesn’t work like that of a code-breaker. Some of the ancient languages I studied were originally decoded by cryptographers who turned their attention to trying to understand people whose only means of communication were forms of writing long forgotten. For me, as a student, it was more a matter of trying to understand what it meant to think like someone else. This may be what is most distressing about the fascist outlook brewing in Washington—there is no desire to even attempt to look at things from the other point of view. It’s a raw celebration of power granted in a moment of weakness. We have tomes and tomes of history to demonstrate just what’s wrong with all of this, but the enigma is that those who have no interest in learning will ever read them. We continue to play a silly political game without counting what we have lost. This may be a zero-sum game after all.