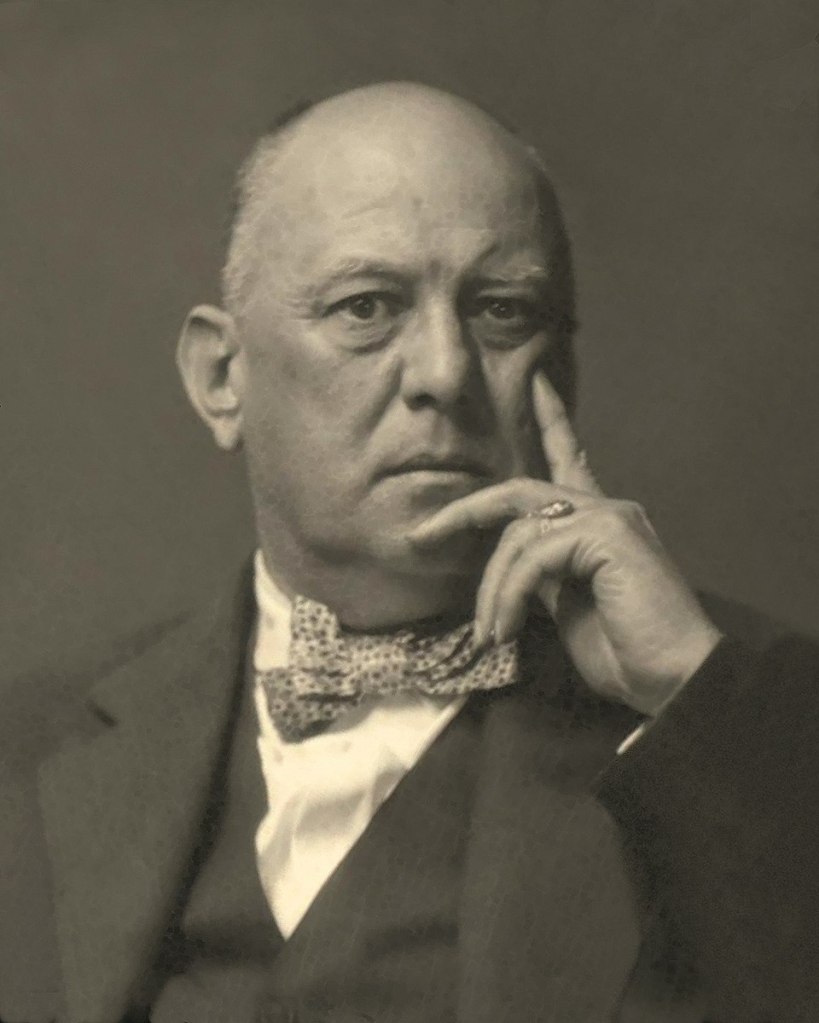

I have to confess to never having read a biography of Aleister Crowley. I’ve known of him since I was a teenager, however, since you can’t read very much about esoteric stuff without running into his name once in a while. Crowley was famous for starting the religion called Thelema, revitalizing interest in magick (the additional “k” was to distinguish it from stage magic), and for generally being a bad boy. In fact, he declared himself the “wickedest man on earth” and liked to be called “the Beast” and loved the number 666. It was the latter point that caught my attention recently. In pop culture, 666 really only took off after The Omen. (Movies often dictate, or at least inform, our religion.) Crowley, who lived much earlier than the film, saw the marketability of 666 and I wondered how it caught his attention.

As I recently posted, the end of the world as we know it is a fairly modern construct. I happened to be reading about Crowley recently and learned that he was raised in the Plymouth Brethren tradition. (They don’t loudly claim him as a native son, for some reason.) He is probably the most famous of the Brethren, across all walks of life. He even earned a place on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The Plymouth Brethren were massively influenced by John Nelson Darby, the inventor of dispensationalism. Dispensationalism is the fairly new Christian belief that time can be divided into ages, or “dispensations,” during which God has a plan already mapped out. He apparently waited for Darby before letting the rest of the world in on this secret.

Things about Crowley then began to make a little more sense. His choice to name himself after Darby’s preoccupations adds up. I haven’t read any biographies so this may be old news, well known among scholars of esoterica. It nevertheless bears pondering because the religion we teach our kids may have unexpected consequences. Crowley rejected the Brethren (whose moral predilections were not to his liking, especially as a hot-blooded young man) but the religion influenced him nevertheless. I wonder if the teachings Crowley received as a child encouraged him to become, in his own mind, the opposite. Crowley wasn’t “the Beast.” His precepts included “love is the law” (granted, his version of love was a touch earthier than Christians with whom he’d be raised, but still), not a bad start for an ethical system. Even the wickedest man on earth believed in the power of love, even if his religion introduced him to 666.