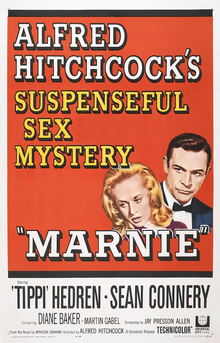

When you can’t have horror, Hitchcock will sometimes do. Having seen most of the big classics, Marnie came to the top of our list, and I found it had some triggers. I suspect that’s true for those who have experienced childhood trauma and who sometimes do things as an adult without knowing why. At least that’s what I took away from it. To discuss this will require spoilers, so if you’re behind on your Hitchcock you might want to catch up first. Here goes. Marnie’s mother was a prostitute who turned to religion. The reason is that one night during a storm young Marnie was frightened and one of her mother’s clients tried to comfort her. Supposing he was molesting her daughter, she attacked him and when he hurt her, young Marie killed him. All of this was repressed in her memory and now, as an adult, Marnie is a kleptomaniac who has the many phobias that that night impressed upon her.

Then along comes Mark. Although he knows Marnie is a thief, he falls in love with her. From a wealthy family, he’s influential enough to get charges against her dismissed, which he does once they marry. He tries to unravel why Marnie won’t sleep with him, why she can’t stand red, why thunderstorms terrify her. In a very Freudian move, he recognizes that her relationship with her mother is the key. Hiring a private investigator, he discovers what happened to Marnie as a child and then takes her to confront her mother. Marnie has never felt her mother’s love, but she didn’t remember the incident and didn’t know that her mother took the murder rap for her and subsequently distanced herself from her daughter.

I have to admit that I found this more disturbing than most Hitchcock films I’ve seen. The ending, which I revealed in the first paragraph, brought quite a few of my own childhood issues to the surface. Parents try to do the best they can, at least most of the time, but we damage our children psychologically, generally unintentionally. And trauma in your youngest years never leaves you. I can mask and pretend—that’s the way you survive in this world—but a number of my experiences as a pre-teen affect me every day, whether I realize it or not. Where I choose to sit in a room. How I respond to unexpected events or sudden changes. Why I immediately have to know what that noise is and where it came from. These are all part of the legacy my childhood left me. I think Marnie would understand.