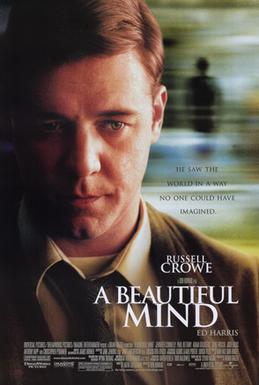

Although it is central to understanding all human experience, we are far from comprehending consciousness. It’s clear to me, based on the fact that our senses are limited, that rationality alone can’t provide us with all the answers. And brilliance often comes at a cost. These were my thoughts after watching A Beautiful Mind. Having hung around Princeton quite a bit when living in New Jersey, it was nice to see it in a film. The movie is, of course, a somewhat fictionalized account of the mathematician John Nash’s life. Although extraordinary in his grasp of math, Nash suffered from mental illness as well. A Beautiful Mind takes liberties, but then, most biopics do. The film is well done from a cinematic point of view, and for those of us without any real knowledge of Nash (although we only lived about 15 miles away) it effectively fools you into mistaking reality.

I wanted to see the movie because it’s often cited as an example of dark academia. Clearly the mental illness—called schizophrenia here—is the source of the darkness. Academia is obvious. This biopic genre of dark academia includes a number of films and many of them explore the disjunction between deep thinkers and social life. It seems that we may be only in the early stages of mapping the intricacies of the human mind. I was recently reading that psychology is still, after all these years, struggling to be considered a “real” science. The human mind is a slippery place and emotion and intuition play into making someone really stand out from the rest of us. And also, their stories have to be noticed by someone. In Nash’s case, a book that was later made into a movie.

Academics in general aren’t given much notice. Many operate in the rarified world of extended study. Those who, like myself, are expelled, often have difficulty fitting in to other lines of work. Thinkers often have trouble not thinking. That can get you into trouble on the job. Movies like A Beautiful Mind have some triggers for me because I often question what reality is. I always have. Please don’t take it personally, dear reader, when I say I’m not sure you’re real. (You may think the same of me.) It’s just the way I look at the world. I’m no mathematician, though, nor a scientist. Not even a philosopher, according to the guild. Academia, however, was my home and seems to have been what my mind was made to do. At this point, I’ll settle for watching movies about dark academia.