One of the most valuable aspects of the humanities is the range they give the imagination. As an undergrad from a small town, I was astonished at the range of courses available in a liberal arts college. Even so, I took only two in the literature department. I wish I’d taken more. You see, as someone who grew up poor, my reading has often been budget reading. Used books found by chance and cheap editions in department stores of a town lacking bookshops. I soon found that Gothic literature met my needs. Alan Lloyd-Smith’s American Gothic Fiction: An Introduction is, as you might guess, a series book. One of those books by an outsider analyzing a different culture’s literature, it is nevertheless quite good for the most part. Until it decides, as many literary studies do, to go all theoretical. Prior to that it’s very engaging.

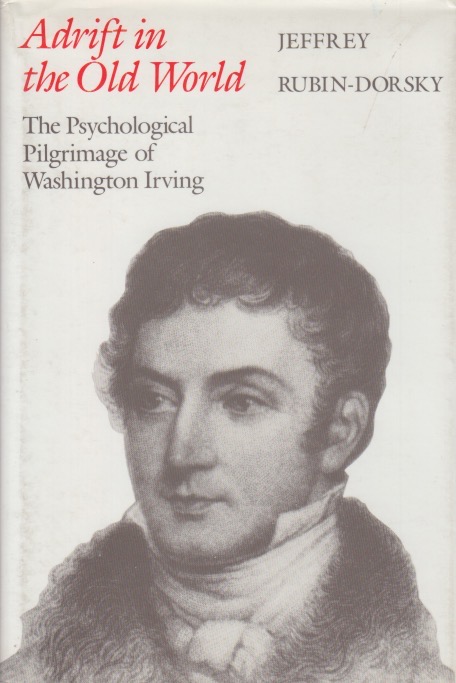

For me it’s less the ideas than the mood of Gothic literature that I find engaging. It creates a cozy feel, and when I read about Poe, Melville, and Hawthorne, I feel a sense of belonging. Gothic transformed when it emigrated to America. Lloyd-Smith does a great job of demonstrating how castles and cathedrals gave way to a landscape built by Native Americans, and an unexplored frontier. How literature in America tended toward the Gothic from the beginning and even up to the point this book was written, hadn’t really effaced much at all. Such things are inspiring to me. It jumpstarted my own fiction writing again. One curious feature, however, is that the book doesn’t discuss “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” at all, other than a passing reference to Burton’s film. There’s quite a lot on Poe and company, Charles Brockden Brown, and some of Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Even Toni Morrison makes an appearance or two. (He does cover Southern Gothic also.)

While this is clearly intended as a classroom book—wide, wide margins for note-taking, introductory level until chapter six—it is worthwhile reading for any curious adult interested in American literature. My life has been a search for my tribe. For many years it was a very religious search, that, unfortunately led to rejection that left me searching for a new home. The horror community has been somewhat welcoming, and there’s something Gothic about that in its own right. In any case, reading about Gothic brings its own melancholy joy. I mostly enjoyed this book and learned quite a lot from it. And, of course I bought it used.