Among the most compelling questions raised by consciousness is “where am I from?” Humans are a species of widely traveled individuals and despite the fiction that we all derive from happily married couples, we often end up distant from our relatives. Over time we may forget who they were. Our descendants, however, may be very curious. I have spent some time, over the years, climbing my family tree. It’s endlessly fascinating because you find that the research is about people’s stories, not just who was coupling with whom. Those of us of non-American ancestry who live in America often wonder how we came to be here. Families preserve stories, and sometimes those stories are embellished over time. I’ve spent more than an afternoon or two in county clerks’ offices thumbing through records to try to push things back just one more generation. Who were these people who led to me?

The Mormons, among other aspects of their theology, have contributed greatly to genealogical research. It is an American religion indeed. My family recently gave me a DNA tracing kit, run by ancestry.com, as a gift. Although it wouldn’t answer all the questions about my background, I suspected it would either confirm or deny some of the stories. The results just came in, and, amazingly, family stories were right about on the mark. I’ve always called myself an “American mutt” but it would have been more accurate to say a “northern European mutt.” Mostly Germanic, English, and Irish, I fit into the typical early settler paradigm. There are minor traces in there that I’m not sure I understand, maybe less than one or two percent—some Asian, some African. All of this will take more research. You never really find out who you are. Completely.

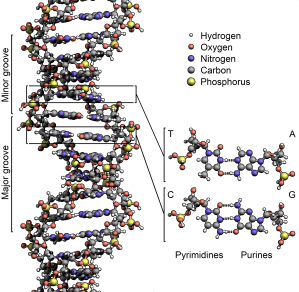

DNA testing is the stuff of science. It isn’t a precise science in that it can’t tell the stories of those ancestors. It takes family tradition to do that. I know that one Irish ancestor stowed away on a ship and she arrived in America not as a paying passenger. I know another branch came as a German engineer and his wife, and that their son opened a bakery. Some of the branches have been here since the Revolutionary War, but they were also germanic—were we Hessians? I haven’t had time to read through all that the Mormons have discovered about me, but I’ve got a pretty good idea that family tradition hasn’t failed me here. While the stories can’t themselves be confirmed by the science, they are not inconsistent with the results. And when it comes to finding out who’s your daddy, the answer really depends on how far back you look.