I recently had cause, for a work project, to survey which Episcopal seminaries are still around. You see, I began my teaching career at Nashotah House. (There were few teaching jobs in the early nineties, although we’d been promised a glut in the late eighties when I set out on that career track.) In any case, I remembered marveling that the Episcopal Church had eleven seminaries. For perspective, one of the largest Protestant denominations, the Methodists, only had thirteen. Enrollments were high in those days. Before the rise of the Nones, seminary teaching was a viable, if perhaps staid, option for a career. Or in the case of some of us, it would be a holding pattern until something more suitable came along. (I’ve always thought of myself as a small college professor.)

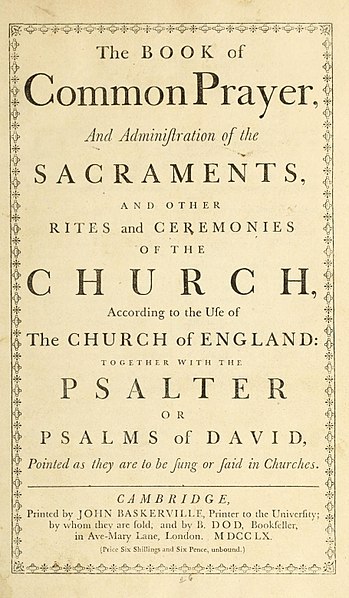

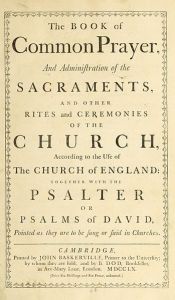

So the list of Episcopal seminaries is now down to ten, but those ten are much diminished from what they were back in the nineties. Seabury, the nearest competitor to the south of Nashotah, has merged with Bexley Hall to make a very small federation. Berkeley at Yale is a Jonah in the whale. Episcopal Divinity School had to vacate campus and merge with Union in New York, leaving the tradition Episcopal stronghold of Boston. The others seem to be clinging on. In the midst of all this I learned that the Anglican Church in North America, a conservative break-away denomination, has reissued the Book of Common Prayer. The BCP, as it’s fondly known, has a long and venerable history. The 1979 edition has both a more conservative and a more modern liturgy, but even that doesn’t seem to be enough to prevent fracturing.

Fracturing. Estimates for the number of denominations in North America set the figure at about 40,000. No wonder Nones are among the fastest growing category! If you’re going to place your eternal salvation on a bet, and there are that many options to choose from, the odds seem awfully long. In some cases it’s a matter of being in the right state, or city, where the “one true church” exists. If you miss it by thirty miles you could end up in Hell. And all this with shrinking numbers. The landscape has changed since I entered the seminary world. Even as the numbers go down the fragmentation increases. From a bird’s eye view this looks pretty odd. Even if you look to the Prayer Book for solace you have to ask which one. I just make the sign of the cross and move on.