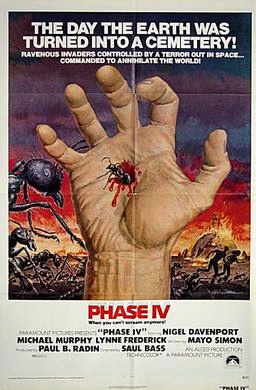

Sometimes I get things backwards. You have to understand that in the pre-internet era finding information was somewhat dicey. Those of us from small towns had limited resources. The movies I saw were on television, with a rare trip to the theater being a treat. Books, on the other hand, could be had for a quarter or less at Goodwill. There I found the sci-fi horror Phase IV by journeyman writer Barry N. Malzberg. I knew there was a movie, which I hadn’t seen, and I assumed it was based on this novel. Actually, the book was a novelization of the movie. But it’s more complex than that. The movie was based on an H. G. Wells story, screen-written by Mayo Simon, then novelized. That novelization made a real impression on me as a kid and I knew that I would eventually have to see the movie.

Some scenes from the novel were still alive to me before watching the film. It occurs to me that maybe you don’t know what it’s about. Intelligent ants. Some cosmic event boosts ant intelligence and two scientists are sent to Arizona to sort it out. A local family ignores an evacuation order, and when one of the scientists destroys the oddly geometric anthills, a war is on. (I remembered the destroying the anthill scene.) The war is both of might and wits. Meanwhile the family is attacked—I remembered the scene of the ants eating the horse—with only a young woman surviving. She’s found by the scientists after the first pesticide is released. The ants attack, intelligently, the research station. We never do see the expected ants popping out of Dr. Hubbs’ infected arm, but it’s clear by the end that the ants have won and we’re living in Phase IV.

A few observations: this is a scary movie, even if seventies’ fare. The sci-fi elements dampen the horror down a bit, but it is still scary. And it also references religion. I watched the movie a few weeks after seeing The Night of the Hunter for the first time. What does a Depression-era serial-killing preacher have to do with ants? The hymn, “Leaning on the Everlasting Arms.” Now, there’s a project out there for someone inspired by (if such a thing exists) Holy Horror. Is there a discernible pattern of how hymns are used in horror? I suspect there is. That hymn is used so differently in these two movies that I’m convinced something deeper is going on. If you’re interested, the idea’s free for the taking. I’ve just spelled out two of the movies for you.