Watching documentaries always seems to raise questions. I recently found A History of Horror with Mark Gatiss on YouTube. Produced by the BBC in 2010, the set of three episodes is a selective walk through the horror genre through the eyes of an insider in the film industry. Divided over three segments, he covers early horror (primarily Frankenstein-related movies), British horror, and the American horror revival beginning in the late 1960s. It occurred to me while watching this that horror is often—but not always—an intellectual genre. Many of the plots and ideas are sophisticated and puzzling. At one point Gatiss says it is nearly the perfect genre for movies. I would tend to agree. Many of the payoffs of horror are the reasons I go to see a movie.

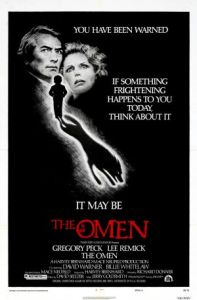

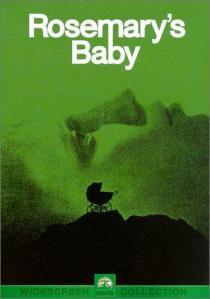

Of course, documentaries involve interviews. While discussing religion and horror—the two are closely related—in the third segment, he considers the impact of what I termed the “unholy trinity” in Holy Horror: Rosemary’s Baby, The Exorcist, and The Omen. His primary interview for this set was with David Seltzer, the screenwriter for the last of these. At this point my memory took me back to an interview on one of the extras for my DVD edition of The Omen. In that interview Seltzer mentions that the antichrist is at that moment (clearly this was shot shortly after the movie came out) walking the earth. In my mind I compartmentalized this to interpret his stance as that of a religious conservative. The idea of the Antichrist, after all, is post-biblical, at least in the sense that end-time scenarios are developed.

The Gatiss interview was filmed many years later and he asked Seltzer if he believed in the Devil. “No,” Seltzer laughed, stating that if he did he wouldn’t work on movies like The Omen. People’s opinions change over time, of course. And the Devil and the Antichrist are two separate characters as they develop after the Bible was completed. Still, I had to wonder if his earlier interview included that comment about the Antichrist being alive now wasn’t intended as a bit of spooky propaganda for the movie. It’s difficult to know what someone really believes. Most people mouth what their ministers say, not really considering where said clergy get their information. For these many years I’ve been thinking that The Omen was considered as some kind of documentary by the screenwriter. Documentaries always seem to raise questions.