“This article may incorporate text from a large language model. It may include hallucinated information, copyright violations, claims not verified in cited sources, original research, or fictitious references. Any such material should be removed, and content with an unencyclopedic tone should be rewritten.” So it begins. This quote is from Wikipedia. I was never one of those academics who uselessly forbade students from consulting Wikipedia. I always encourage those who do to follow up and check the sources. I often use it myself as a starting place. I remember having it drilled into me as a high school and college student that in general encyclopedias were not academic sources, even if the articles had academic authors. Specialized reference works were okay, but general sources of knowledge should not be cited.

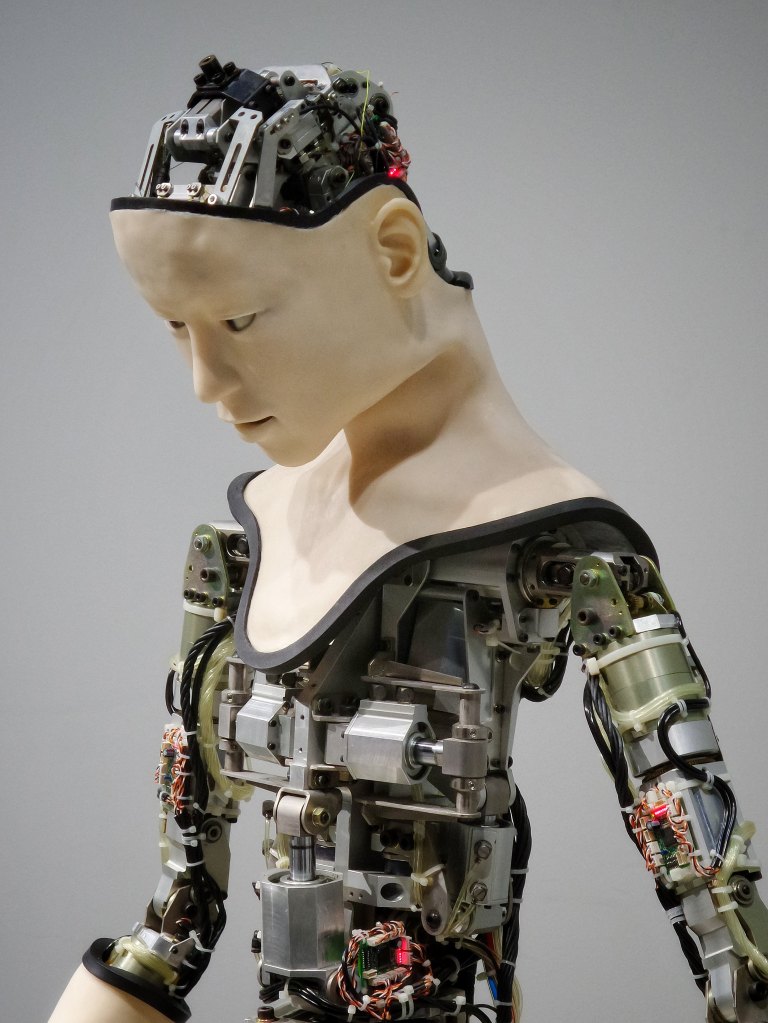

The main point of this brief disquisition, however, is our familiar nemesis, AI. Artificial Intelligence is not intelligence in the sense of the knowing application of knowledge. In fact, Wikipedia’s warning uses the proper designation of “large language model.” Generative AI is prone to lying—it could be a politician—but mostly when it doesn’t “know” an answer. It really doesn’t know anything at all. And it will only increase its insidious influence. I am saddened by those academics who’ve jumped on the bandwagon. I’m definitely an old school believer. So much so that one of my recurring fantasies is to sell it all, except for the books, buy a farm off the grid and raise my own food. Live like those of us in this agricultural spiral must.

A true old schooler would insist on going back to the hunter-gatherer phase, something I would be glad to do were there a vegan option. Unfortunately tofubeasts who are actually plant-based lifeforms don’t wander the forests. So I find myself buying into the comforts of a life that’s, honestly, mostly online these days. I work online. I spend leisure time online (although not as much as many might guess that I do). And I’m now faced with being force-fed what some technocrat thinks is pretty cool. Or, more honestly, what’s going to make him (and I suspect these are mostly guys) buckets full of money. Consider the cell phone that many people can no longer be without. I sometimes forget mine at home. And guess what? I’ve not suffered for having done so. The tech lords have had their say, I’m more interested in what people have to say. And if Al is going to interfere with the first steps of learning for many people, it won’t be satisfied until we’re all its slaves.