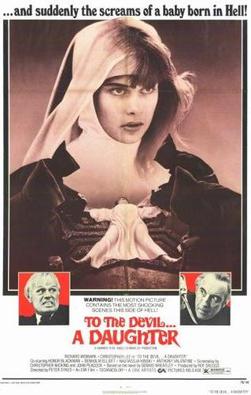

Any movie that begins with an excommunication ought to be good. Especially with its list of stars you’d think To the Devil a Daughter might’ve turned out better. Still, it is a good example of religion and horror mingling together. I’ve never read any Dennis Wheatley novels, but reputedly he didn’t like this film adaptation of his book. It certainly has a convoluted plot. So an excommunicated priest has started a new religion that worships Ashtaroth. He has to baptize a child, now 18 (three-times-six, don’t you see), with the blood of the demon so that she can become his (Ashtaroth’s) avatar. This is apparently the eponymous daughter to the Devil. She was baptized initially by her mother’s blood at her birth.

The girl’s father, who survived her birth—unlike his wife—has decided at the last moment to save his daughter. He appears to be independently wealthy yet he talks an author of occult books into doing the saving for him. The girl, it turns out, is a nun in this satanic religious order and is only too willing to do what she can to serve “our Lord.” The way that all of this plays out is confusing and Byzantine, but it does raise a serious question: what if a child is reared in a bad religion? (And there are some.) Who has the right to decide if a religion is good or bad? Children are easily indoctrinated and not too many question the faith in which they were raised. Yes, we all think the religion we believe is the right one. The problem is everyone else thinks the same thing.

One of the things this movie got right is that the “heretics” are portrayed as sincerely believing that their religion is for the improvement of the world. Calling themselves Children of the Lord, they believe Ashtaroth is good. And a good lord wants what is best for the world, right? This is the dilemma of exclusive religions that teach only their own outlook can possibly be the correct one. Otherwise you have to give adherents a choice and another religion may be more appealing. Or worse, they may reason out that if you’re given a choice that means your own religion is also merely one of many. Historically religions have gotten around this by valorizing true believers who never question anything. To the Devil a Daughter isn’t a great movie. It’s not even a very good one. Nevertheless, it raises some questions that lie, of course, in the details.