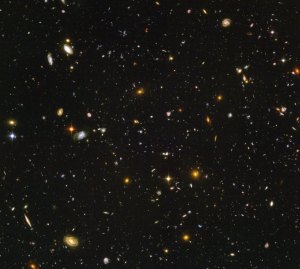

Let me send out a warm welcome to the neighborhood, I think. Not that I officially represent Earth—or anything for that matter. I’m just friendly, I guess. Now that astronomers have strong evidence that the nearest star to our own, Proxima Centauri, likely has a planet, it’s not premature to head over with a casserole. It’s not every day that a new solar system is discovered. We don’t know for sure that the planet’s there, but chances are pretty good. In reading about this discovery I learned that the orthodoxy has changed since I took astronomy in college. It seems now standard wisdom teaches that most stars likely have a least one planet. I can’t even count the stars—I usually start to trail off after I get to about ten—so I can’t imagine the number of potential planets out there. And where there are planets, there are gods.

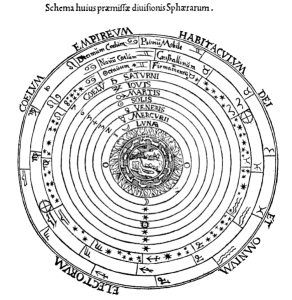

Let me rephrase that. If there are billions and billions of planets it is very likely that there’s life out there. I know I’m racing ahead of the evidence here, but let me have my fun. If there’s life, there’s a chance, a glimmer of a chance at least, that given enough life we’ll find consciousness. I’ve always thought it was a touch arrogant on our part to assume we were the only ones out here. Perhaps it’s because the stakes are so, ahem, astronomically high we seem to be afraid to admit the possibility. We don’t really want to be alone in this cold, vast, universe after dark. Enter the gods. Conscious beings—even arrogant ones—have no trouble supposing that there is an even greater presence out there. I suspect this isn’t an earth-bound bias. I should hope that conscious life looks toward the stars with wonder, and even after they discover that there’s no lid on their planet they might still ponder what else might be out there.

Let’s suppose there are other creatures out there with other gods. When the meeting takes place we’ll need to have that discussion. You know the one I mean. We’ll need to ask whose deity is really real. Is it yours or is it ours? Hopefully we’ll enter into this with an open mind. I suspect it will depend on who’s in the White House, and all the other big houses, at the time. There are certainly those who claim their own almighty brooks no rivals. If it turns out that we can’t agree, I hope it doesn’t come to blows. There will always be other planets to explore, and maybe even new orthodoxies to accept. It’s an infinite universe, after all.