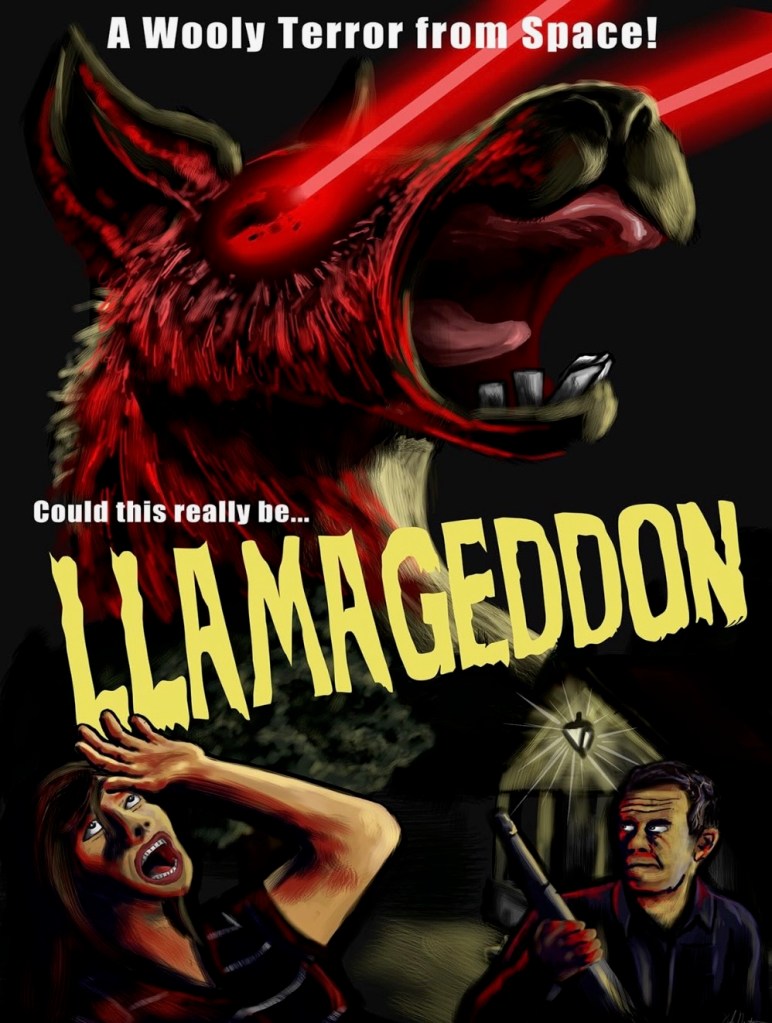

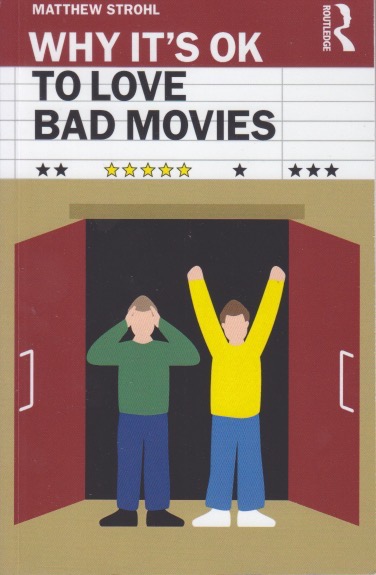

After anesthesia they tell you, “Don’t make any important decisions.” That’s the excuse I’m using for having watched Llamageddon recently. That, and it’s free on one of the streaming services to which I have access. I only found out about it because of such services and I wasn’t in any shape to decide important things like how to spend the rest of the groggy day. I’m of mixed minds regarding comedy horror. Or is it horror comedy? Decisions. The fact is, quite a few horror movies do involve some amount of fun. My favorite ones tend to be more serious, but once in a while you find yourself watching movies you know are (or you know are going to be) bad. I knew this one was. It’s so bad that it’s got a cult following. It was, I’m pretty sure, made to be bad.

So a killer llama from another planet is forced to land on earth. It kills an older couple in Ohio and after the funeral two of their teenage grandchildren, Mel and Floyd, are left to stay in the house. Mel, who is older and more experienced, contacts all her friends so they can party that night. Of course, the llama’s still on the loose. It has laser-beam eyes and it bites and punches people to death and the partiers are picked off, not exactly one-by-one since many of them are electrocuted in the hot tub. Generally they’re so drunk and/or high that they don’t believe any of this is happening. Eventually Mel and Floyd’s father arrives and tries to save his kids. Before dying of llama bite, he kills the quadruped by running it through a combine.

It’s worse than it sounds, but it’s played strictly for laughs. And, I suspect, it’s one of those movies that’s meant to be watched under the influence. Since anesthesia is about as close as I’ll ever get to that, I suppose this counts. Some of the early horror movies have become funny with the passage of time as early special effects age and we become used to better, more convincing fare. As it is, it’s difficult to find much about Llamageddon apart from IMDb, and the director’s name, Howie Dewin, is a red herring. I’m fascinated by such films being able to gather a following. Of course, I confess to enjoying Attack of the Killer Tomatoes when the mood is right. And a day when decisions are contraindicated, anything can happen.