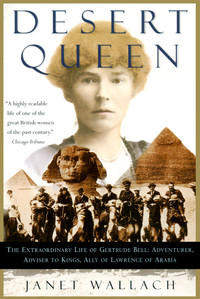

Gertrude Bell requires no introduction for students of the ancient Near East. A strong-willed, self-determining woman, her influence was arguably as great as that of her friend T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia), but being a woman in a man’s world, movies were not framed around her life and she was not mythologized into a larger-than-life character. I have just finished Desert Queen by Janet Wallach, the life story of Gertrude Bell. Although tending towards the overly romantic in parts, this biography does a fine job highlighting the influence Gertrude Bell had on the newly formed country of Iraq at the close of the First World War.

Gertrude Bell requires no introduction for students of the ancient Near East. A strong-willed, self-determining woman, her influence was arguably as great as that of her friend T. E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia), but being a woman in a man’s world, movies were not framed around her life and she was not mythologized into a larger-than-life character. I have just finished Desert Queen by Janet Wallach, the life story of Gertrude Bell. Although tending towards the overly romantic in parts, this biography does a fine job highlighting the influence Gertrude Bell had on the newly formed country of Iraq at the close of the First World War.

Although Gertrude early lost her mother she was a child of a well-to-do English family. She was considered an anomaly at a still patriarchal Oxford in her day, but soon discovered the draw of the Arabian and Syrian deserts. Traveling seemed to be an antidote for being a capable woman in a man’s England. In the desert the sheiks and tribal heads came to treat her as an equal, like a man. (T. E. Lawrence, on the other hand, was famed for occasionally pretending to be a woman.) Assigned a government post in post-war Iraq, she helped draw up the borders of the present nation of Iraq and achieved a status with the desert tribes to which few of her male colleagues even aspired. Failing in health and fortunes, lonely in the desert she loved, Gertrude Bell committed suicide in Baghdad and was buried in the land she loved.

The story of Gertrude Bell is inspiring despite its sad ending. Here was a woman who refused to accept the model society cut out for her gender. Part of her loneliness resulted from her staunch unwillingness to be like other passive, subservient women of her time. After the reigns of political power slipped from her hands, Gertrude Bell founded the Baghdad Museum, collecting the initial artifacts herself and donating a substantial portion of her remaining funds to the museum in her will. Until the “Second Gulf War” it was the finest collection of ancient Mesopotamian artifacts in Iraq, where culture itself began. Gertrude Bell’s books are still read, but she is still known primarily as the associate of Sir Leonard Woolley and Lawrence of Arabia, although she was a woman on her own terms. She remains a symbol of what might be accomplished even when the standards of society declare a person unfit to lead based on gender or any other physical attribute.