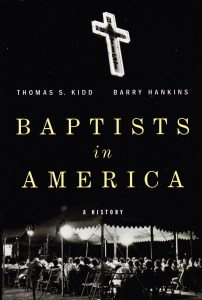

Few things distinguish American Christianity as much as its divisions. These aren’t precise, however, and often the borders are fuzzy and held more by cultural history than by theological outlook. One of the denominations—indeed, the umbrella for the single largest Protestant denomination in America—often faces the question of its identity. Who are the Baptists? Many Protestant groups can trace their histories to defining moments; consider Martin Luther and his hammer, according to the Lutheran origin myth. Baptists are a little tricker to pin down. Dissenters, yes, convinced that adult baptism should accompany conversation, yes, but beyond that widely divergent. Thomas S. Kidd and Barry Hankins have provided a service by writing Baptists in America: A History. Going back before America, they trace the origins of the sect and quickly bring it into the context in which it would thrive.

Few things distinguish American Christianity as much as its divisions. These aren’t precise, however, and often the borders are fuzzy and held more by cultural history than by theological outlook. One of the denominations—indeed, the umbrella for the single largest Protestant denomination in America—often faces the question of its identity. Who are the Baptists? Many Protestant groups can trace their histories to defining moments; consider Martin Luther and his hammer, according to the Lutheran origin myth. Baptists are a little tricker to pin down. Dissenters, yes, convinced that adult baptism should accompany conversation, yes, but beyond that widely divergent. Thomas S. Kidd and Barry Hankins have provided a service by writing Baptists in America: A History. Going back before America, they trace the origins of the sect and quickly bring it into the context in which it would thrive.

Persecuted early in American life, Baptists grew in numbers and recognition during the period commonly known as the Great Awakenings. Suited to frontier individualism, non-doctrinal, and advocating for freedom of conscience, the Baptists gained large sums of converts in this era. With their congregational polity, Baptist cultural influence really only took off when mass media gave its more aggressive preachers a venue not limited by church walls. As Kidd and Hankins point out, however, the denomination proved friable. Splitting apart over various issues, the number of Baptist denominations grew. Their political influence would also grow so that they would become a force with which to be reckoned even today. Few, however, really understand who the Baptists are.

The Southern Baptist Convention is the largest single Protestant denomination in the United States. It defines itself by a radical conservatism that masquerades as “orthodoxy.” Heavily biblical, many in the tradition have a strong preference for inerrancy. Social causes that appear outdated to most modern people are do-or-die issues for this sect within a sect. Baptists in America does a good job showing how contradictory Baptists can be. They were, after all, dissenters from the beginning. Their championing of religious freedom often doesn’t apply outside their own borders. The more political of the denomination know very well how to game a democratic system. Perhaps the lesson they’ve learned most acutely is that being unseen carries with it great advantages. They play the sport of legislative chess very well. In a culture that loudly and repeatedly claims that religion no longer matters, those with conviction have a natural hiding place. From there pieces are easily moved to positions of power.