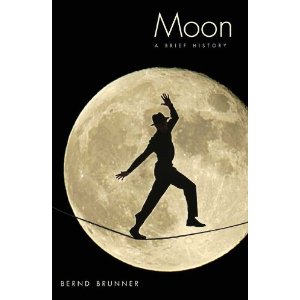

Long venerated as a god, the moon has fallen to such a declination that it scarcely attracts the notice of most people anymore. While some governments are busy making plans to reach the moon—notably those with the largest populations—the rest of the developed world looks to the nighttime sky and lets out a yawn. The poignant little book called Moon: A Brief History, by Bernd Brunner, offers a moving tribute that is part science, part history, and part whimsy. Very few heavenly bodies have undergone the dramatic plummet in interest as our familiar old moon. It remains the proximate cause for werewolves and the occasional harvest-season horror movie, but since the Cold War has ended and we no longer need to prove ourselves to anybody, attention has shifted toward more distant and abstract targets. Maybe Mars, or one of Jupiter’s moons holds the fascination we so long for. The moon, apart from a brief flare of interest when water was discovered there, has died a slow death in the human imagination.

In ancient times, the moon was often considered superior to the sun. Sure, it’s not as warm—downright cold at times—but its light is more gentle, more forgiving. The traveler’s companion, the moon illuminated the way before headlights were invented. The god of the moon (its gender was slippery in parts of the ancient Near East) sometimes topped the pantheon. Even today in Islam, the memory of the high god’s crescent moon can be found atop mosques throughout the world.

What happened to the moon? Famously Carl Sagan, himself an astronomer, wrote about The Demon-Haunted World. In this book he decried the human tendency to look for supernatural causation; the universe is entirely natural. Many have used his reasoning as a nail in the coffin of God. Clearly he was right in many cases, but, as Brunner shows, science can rob even a deity of its shine. Writes Brunner: “Its significance and roles have always varied across cultures and eras—from heavenly god to symbolic guardian or judge, to the scene or stage of spectacular visions and visits, to being ‘just’ and object of scientific investigation.” Once we’ve been to bed with the moon and look at it scientifically, its luster is lost. “Maybe we should try sometimes to un-think our scientific knowledge of the moon,” Brunner opines.

I was one of those thousands planted before the television on 21 June 1969 to watch the first men on the moon. Amid the turmoil of earth, it was a sublime, even a religious moment. In the end a dozen men walked on the moon before it was forgotten. Like the dozen disciples, they alone have been near the truly sublime. With Brunner I too would suggest that we not be too quick to forget our constant companion.