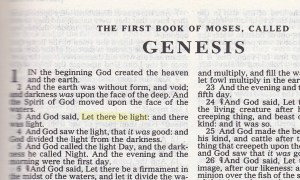

Attempting to write a blog post everyday on the single subject of religion can be a challenge when you don’t share the freedom of the Internet with most faculty. Once in a while a topic just drops in your lap like a gift from God. It helps that New York City is such a religious place. Despite the many critics who claim New York is godless and completely secular, it my experience there are a goodly number of the godly in it. It is not uncommon to see street preachers on a sunny day (apparently God has less need of saving on rainy days). On my way home from work today I was presented with a tract in which “God Answers Your Questions.” It was a little odd that the acolyte with the tracts knew what my questions were, but since the leaflet quotes extensively from the Bible it must be true. From this pamphlet I learned what my hidden question were.

The first question, rather flatteringly, states, “I am young yet, and likely to live for a long time.” Once I’ve been buttered up, the other shoe drops: “Why should I think of eternal things now?” Rather than the Bazooka Joe Bible verse, I thought I might field that one myself. I grew up thinking about eternal things on a nearly daily basis. By the time I was in high school I was somewhat creepy about it. In a college course on the psychology of death and dying, we were asked how often we thought of death. My honest answer was, “every day.” Now, a person with that kind of background may be overthinking this a bit. Death is a relatively simple matter: you need do nothing to achieve it eventually. I had been taught that if you worked to make sure you were honest and true, it would be rewarded. I was fired from my first job for being true to what I’d learned with intellectual honesty. I thought about death a lot.

Death, given its finality, is a universal religious concern. Some religions offer an afterlife—generally it is not an option—while others do not. The life well-lived is its own reward. Others suggest what seems to me a more insidious option: reincarnation. Those religions that take this approach are generally honest up front, stating outright that life is suffering. Reincarnation is goal-directed: break the cycle and achieve Nirvana. And there is no reason to flatter people with the long life yet ahead of them. The evangelist ignored my white whiskers and gave me an anonymous tip for salvation. Perhaps all I really needed was a sip of cold water. Having spent the better part of one life thinking about its end, reincarnation could be a cruel reprisal indeed. I don’t need to worry, however, because I’ve got the answers—along with the questions—right here in my pocket.