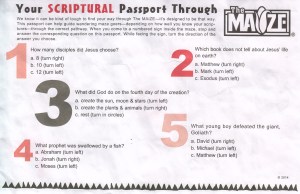

A friend recently sent me a story from Anonymous titled “Why Did The Vatican Remove 14 Books From The Bible in 1684?” This piece reminded me of just how rampant biblical illiteracy is in this Bible-worshiping culture. To begin with the obvious, Roman Catholics are the ones who kept the Apocrypha in their Bibles—it was Protestants who removed the books. No doubt, retaining the Deuterocanonicals was a rear-guard action of the Counter-Reformation, but still, if you’re going to complain about the Papists it’s best to get your biblical facts straight. The story is headed with a picture of The Key to Solomon’s Key. Ironically, Solomon’s Key is actually an early modern grimoire that the author seems to think is the same as the Wisdom of Solomon, one of the books of the Apocrypha. Reading through the post it was clear that we have an Alt Bible on our hands.

(For those of you who are interested in the Key of Solomon, my recent article in the Journal of Religion and Popular Culture on Sleepy Hollow discusses the Lesser Key of Solomon, a famous magic book. It features in one of the episodes of the first season of the Fox series and, I argue, acts as a stand-in for the iconic Bible. One of my main theses (don’t worry, there aren’t 95 of them) is that most people have a hard time discerning what’s in the Bible and what’s not. But I obviously digress.)

The post on Anonymous states that the Bible was translated from Latin to English in 1611. The year is partially right, but the facts are wrong. The translators of the King James Bible worked from some Greek and Hebrew sources, but their base translation was the Coverdale Bible which had been translated into English and published some eight decades before the King James. Myles Coverdale relied quite a bit on German translations, but the King James crowd went back to the original languages where they could. The KJV was published in 1611, but the translation from Latin was actually something the Catholics preferred, not Protestants. The Vulgate, attributed to and partially translated by Jerome, has always been the favored Roman base text. Ironically, and unbeknownst to most Protestants, the King James translation did include the Apocrypha. I like a good conspiracy theory as much as the next guy, but they certainly make a lot more sense when the known facts align without the Alt Bible unduly influencing the discussion.