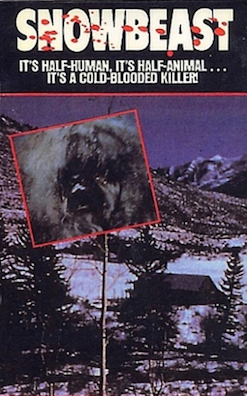

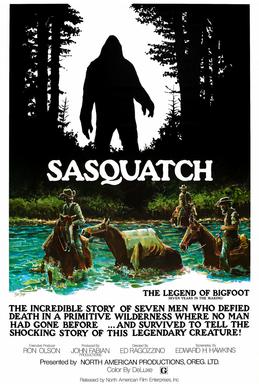

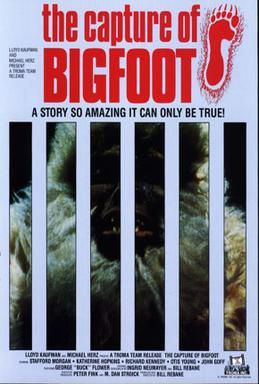

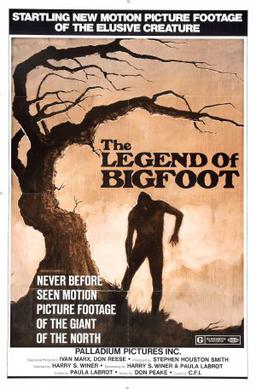

There’s a deep satisfaction at attaining a goal, no matter how low the bar. Having rediscovered the “Beast Collection” after looking to see if Snowbeast was on it—it was missing from another DVD collection I have—I determined to watch my way through. It took two or three months, maybe four, but I finally finished it out with Snowbeast itself. One of a spate of Bigfoot films from the seventies, this was a made-for-television movie. Many retrospectives show a movie going up in critical estimation over the years, but this one seems to have sunk down into the “bad movie” category. But still, of the seven (!) Sasquatch films in the pack, it is clearly the best. A low bar, as I say, but still, it has the advantage of being relatively well written. Joseph Stefano, who wrote the screenplay, was one of the minds responsible for The Outer Limits. He also had credit for writing the screenplay for Psycho.

Decent writing can help redeem bad movies. But more than that, you can actually care for the characters. In some bad movies you have a difficult time raising any feeling for the people portrayed—that’s true for more than one of the other films in this collection. Here are people that doubt themselves, but have good hearts. The story isn’t complex (one of the reason modern critics scorn it). A ski resort in Colorado—much of the movie shows people either skiing or snowmobiling—a young woman is killed by the eponymous snowbeast. When the owner of the lodge insists on keeping it open for a festival, the current manager (her grandson) is reluctant to kill something that’s so human. There’s a bit of a moral quandary here, which provides some traction on a slippery slope.

The beast then kills a member of the search and rescue team, and they know they have to destroy it. The principal characters track it down, and after the beast gets the sheriff, they shoot it. As I say, not much of a plot, but the characters have some depth. It’s not a great movie by any stretch, but it doesn’t leave you feeling as if you’d have more enjoyed doing your taxes. And that’s saying something for a collection of movies that cost less than most single DVDs. Now if that makes me sound old, keep in mind that this movie was from the seventies. And even if most re-appraisers think it has grown worse over time, I’m willing to disagree. After all, I just accomplished something by watching it.