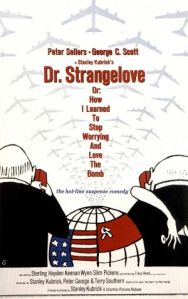

In honor of the fifty-year anniversary of the release of Dr. Strangelove this past week, my wife and I sat down to rewatch the movie this weekend. Psychologically, as Kubrick found out, dark humor was the only way to deal with the sense of doom that pervaded the world into which those of my generation were born. Nuclear weapons had been developed and the Cold War was in full swing. Somehow, even in small-town America, I didn’t find Communism to seem so awful. After all, I grew up reading the Bible and it sounded quite a bit—at least in theory—like the arrangement the apostles had made in the book of Acts. The idea of private property, the very spine and muscular system of capitalism, was considered a sure way to lead to God’s kingdom not being established on earth. Nevertheless, that is the way, as the phrase goes, that the money went. And Communism threatened the right of one percent to horde all the money, so we were ready to annihilate all human life for it. Talk about taking your marbles and going home! No child should grow up knowing the meaning of the phrase “mutually assured destruction.”

Dr. Strangelove has held up well for the half-century since its release. Despite the thawing of the Cold War, the big chill isn’t over yet. And humor still seems the only way to keep sanity and deal with the state of the world. There are still many General Turgidsons out there (some of whom have held very high government offices, and this is no joke). There are at least, as far as we know, fewer General Rippers. So we hope. As the bomber crew nears its target, Major Kong goes over the contents of the government issued survival kit, among which is a comically small Russian Phrase Book and Bible combined. Kubrick, a master of satire, has the godlessness of Communism thrown time and again across the lips of the hawks. It is better to kill everyone than to allow the godless to rule. Even the Bible, however, shares space with the Russian phrasebook, making us wonder whether it is a tool of conversion or an admission of inevitability. Still the bomber, piloted by a Texan, flies on.

Perhaps the biggest moral dilemma we face is our ability to destroy hope. Capitalism promises opportunity to all. Like many who grew up poor, however, I have found lies hidden in plain sight. It is not easy to move ahead if you choose to mire yourself in debt to get an education. In fact, if you lose a job in higher education you can easily find yourself adrift for a decade or more, not earning any retirement money and being frequenly sought out by your local universities as an adjunct instructor. In fact, at many points your career might look like the end of the world. So it is that I take great comfort in settling down to watch Dr. Strangelove again. At least it is an honest movie, and that hasn’t changed in the past half-century. And I think I may have been wrong about how few General Rippers there really are.