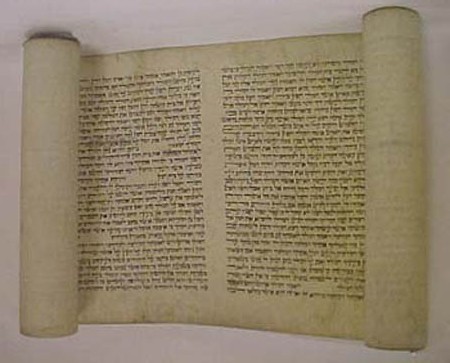

Sometimes you’re not born among your tribe. I live where I’ve moved out of economic necessity, not where my family’s located. My family’s not quite sure what to make of me anyway, so I seek my tribe. At first it was among the United Methodists, but when I was in seminary they let me know what they really thought of me. The Episcopalians seemed more welcoming to my academic aspirations and my doctorate led me to believe my tribe was those who studied ancient West Asian religions. I wrote papers, led conference sections, knew people. When I had to step out of academe, however, they tended to fall away. (Ironically my most-read work, according to Academia.edu, is my dissertation, revised edition. It has had over 8,000 views.) I still have many scholar friends, but I’m clearly no longer part of the club.

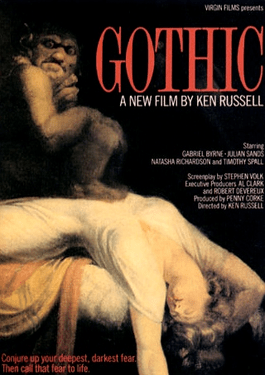

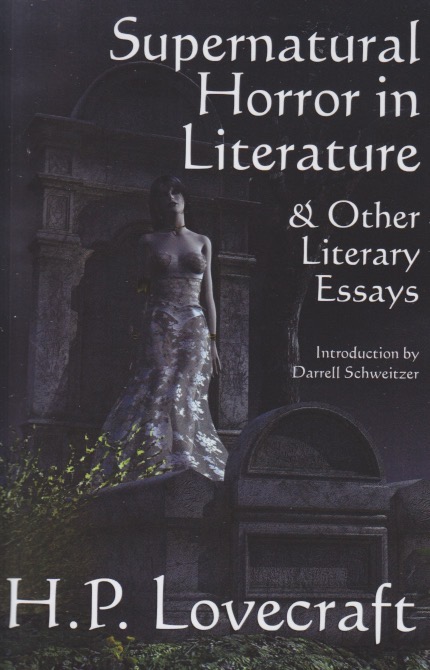

That’s why I turned to horror (as a field of study). I was seeking my tribe. I wasn’t at all sure Holy Horror would get published. I was encouraged when The Journal of Religion and Popular Culture published “Reading the Bible in Sleepy Hollow.” Then I discovered other academics (still not part of the club) were studying religion and horror. Ironically, it was people on the horror side, rather than the religion side, who made me feel most welcome. In the meantime, I wrote some horror stories (still do) but the fiction publishing tribe seems to be at war against the rest of the world. You can’t breach their bulwarks. I’ve been trying for a decade and a half. So I continue to write books that move more toward horror, and move away from religion. Still, hard-core horror fans don’t really pay much attention to my books, still I try, but as an outsider.

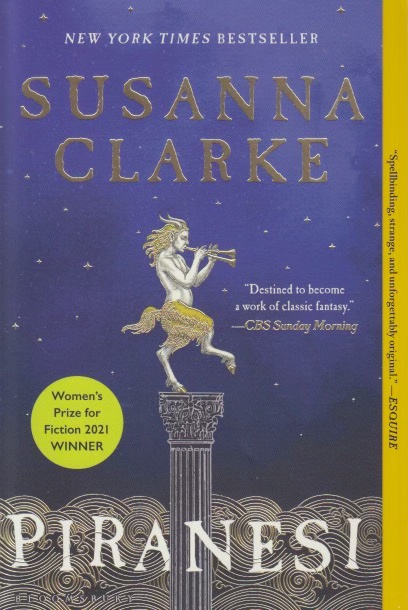

Since Sleepy Hollow as American Myth is in production, I’m working on my next projects. I’ve been indulging in fiction again, where I’d really rather be, for a host of reasons, but unless I succeed as a double agent, I’ll remain unpublished. My tribe, I think, would welcome more nonfiction like I’m writing. These books haven’t been selling well, but they may eventually get referenced. Now, many years after the fact, the ancient West Asian studies tribe cites my work and asks me to contribute more. I’m afraid that island was abandoned years ago, former tribe-mates. I was lonely and so I rowed across the ocean into horror territory. If you’re looking for a tribe too, I’ll be glad to try to introduce you around.