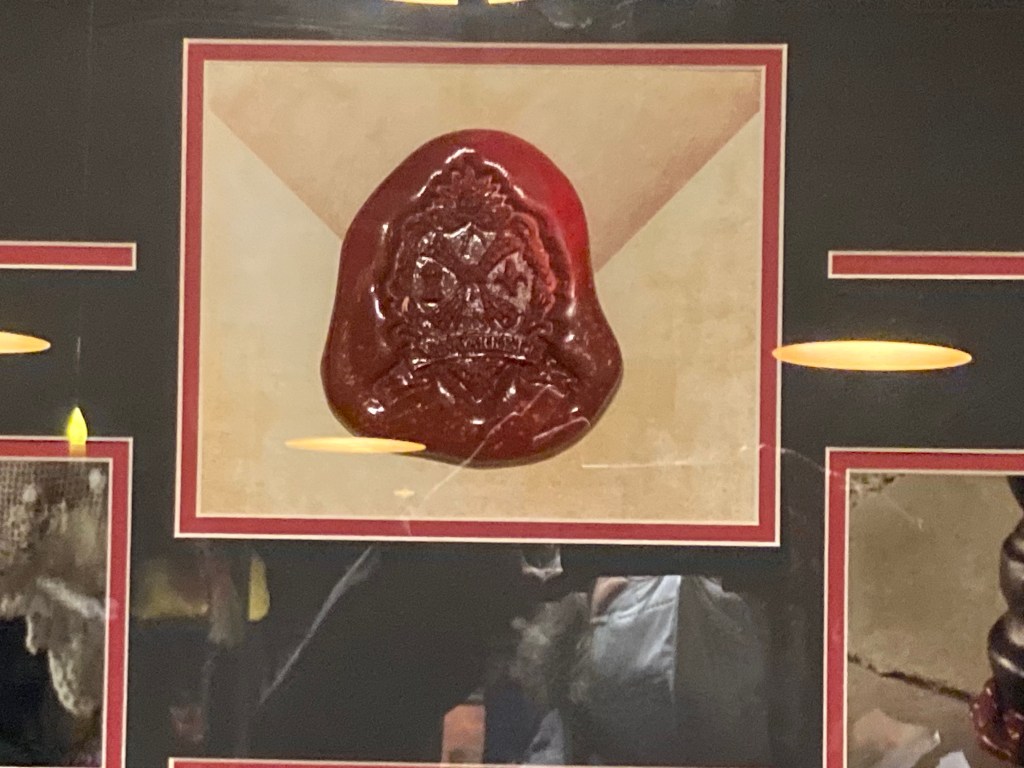

Often making lists of dark academia movies, The Skulls plays right into that territory. A secret society, an elite college, and something’s definitely gone wrong. It’s not a great movie, feeling somewhat contrived, but it fits the mold pretty well. Things are a little too pat in the film, and the writing isn’t the best. It’s entertaining, if overblown. The story begins at an unnamed Yale (actually University of Toronto) with working-class Luke being invited to join the Skulls after an impressive rowing competition victory. From the first, the Skulls meetings seem to lack gravitas. Rich and powerful, they are above and beyond the law. The problem for Luke is that his friends, Will and Chloe, are being edged out of his life. Will, who writes for the school paper, breaks into the Skulls headquarters but is caught by Caleb, Luke’s “soul mate.”

Will is killed in what follows, and Luke wants to get out but it’s too late. Caleb’s father is the head-honcho for the Skulls and decides to have Luke committed to an asylum when he refuses to cooperate over his friend’s death. Chloe and the second-in-command of the Skulls, Senator Levritt, rescue Luke and he challenges Caleb to a duel. I’ll leave it off there so as not to spoil too much. That gives you a sense of the darkness, in any case. But the film doesn’t feel that dark. Yes there is a murder, and there are bad guys, but something I can’t define prevents it from having the tone that you might expect from a grim tale. As I say, things are a little too pat. The characters’ emotions are a little too close to the surface.

The movie did well at the box office, but the sequels were released direct to video. As far as the academia side goes, there are, no doubt, secret societies. Privilege doesn’t let go once it gets a grip. But the above-ground “Yale” sees a bit too light and airy. Maybe more classroom and library scenes might’ve helped. Likely it would’ve been better had it been based on a novel. Films that are based on books have a solid development on which to stand and it’s often a matter of figuring out what to omit. The writer and director had gone to Yale and Harvard, respectively, and wanted to portray what secret society life is like. But that’s the thing about secret societies—you can’t really know, can you? It’s a matter of imagination. And dark academia is where such things fit.