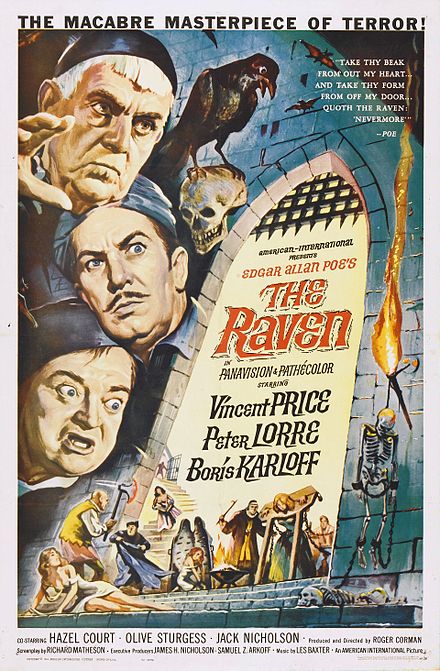

Although we prefer typecasting—it’s so much easier!—Edgar Allan Poe had both depth and width as a writer. He penned funny as well as scary, love poems and detective stories, even something like a scientific treatise. One thing I’m sure he didn’t anticipate was his name being suborned for cheap horror movies. Roger Corman is a Hollywood legend—a good example of a guy making it in the film industry on his own terms. He paired Vincent Price with a number of Poe titles that had little to do with the actual works of the writer. One that oddly stayed with me since childhood is The Raven. This was well before I’d read the poem. It’s funny how very specific things will stick in your mind. I remembered the strange hat Price wore. And I remembered—misremembered, actually—Price using a spinning magical device with sparklers. Misremembered because that was Peter Lorre’s character, not Price.

That was it. I didn’t remember that Boris Karloff was also in the film. I was too young (as was he) to recognize Jack Nicholson as well. Although I watched The Twilight Zone, I didn’t realize the script was by Richard Matheson. This film was loaded with talent, but it really was goofy. I recollected Price was a magician, but I didn’t know this was a rather silly battle to become chief magician. Lorre’s ad libbed lines were surprisingly funny, even after all these years (I was about one when the film came out). Surprisingly, the movie did well at the box office, despite its taking a sophomoric approach to perhaps Poe’s most serious poem.

I’d avoided watching it again for all these years because of that sparkler scene. I’m not sure why that particular moment wedged itself so firmly in my young brain. It seemed so not Poe that I couldn’t get back to the movie, apparently. With Price and Lorre camping it up—Karloff was, by all accounts, most professional as an actor—and Nicholson uncharacteristically timid, the cheap special effects, it’s obvious that viewers enjoyed a good laugh at this one. It’s not true to Poe, of course. It’s true to Roger Corman, however, a filmmaker who knew how to deliver cheaply and quickly and still earn some money at it. I’d last seen The Raven about half a century ago. I may be tempted to watch it again, after having seen it as an adult, but if I wait too long I’ll need to leave that duty to someone who’s read this and who isn’t afraid of sparklers.