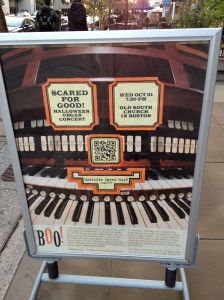

My last night in Boston found me in Copley Square. This has always been one of my iconic Boston locations; something in the juxtaposition of squat, solid, dual-toned Trinity Church with its wide, open plaza, the blue glass razor of the Hancock Tower, and the classical facade of the Boston Public Library where Sophia broods over the world, arrests my wondering gaze. Across Boylston Street stands the gothic Old South Church like a guardian for straying souls. As I walked through the square a local band of street musicians jammed and the first neons of an October evening were awaking. As I strolled past Old South I had to back up a step or two to see if I’d read the sign right.

Scared for Good, a Halloween organ concert featuring spooky music, will soon be on offer. Business-types have long noted that Halloween is a great potential selling holiday. With kids who want to dress up and parents stressed for time, the selling of costumes has grown into an increasingly substantial accessory item holiday. People want their houses to look scary, knocking down real cobwebs to make way for the artificial ones, hanging out orange and purple lights, and ordering pre-carved, artificial pumpkins. All the fear is, of course, a charade, and we laugh at ourselves for taking it too seriously. Some churches object vociferously to the very holiday itself, claiming it is devil worship and evil.

While Halloween does have some serious pagan influences, it is, in its present form, a good Catholic holiday. The night before All Saints, aka All Hallows, begins a period of reflection on mortality. I’ve celebrated “Protestant” Halloween from my youngest days and have never been in any way tempted toward devil worship. It is fun to be scared when you know it’s not real and it won’t last long. That’s why I applaud Old South Church’s Scared for Good concert. Reading the list of pieces included, it sounds like it should be a grand time. Too bad I won’t be in Boston for the occasion. As I walk back to my hotel in the chill of the evening,the only fear i feel is that moments like this evening come at insufferably long intervals for those who feel about the city as must the denizens of Copley Square.