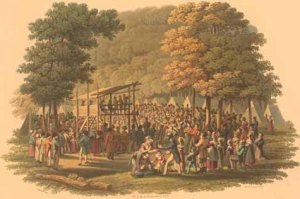

As I was reading Brian Pavlac’s Witch Hunts in the Western World, I learned about klikushi, or “shriekers.” These were Russian “witches” who appear as early as the seventeenth century and who are characterized by screaming, “wailing, barking, and writhing during worship services” (184). In that day this was taken to be a sign of witchcraft and women were arrested and tried for it. Fast forward a century or two. In the wilds of Kentucky what is generally called the Second Great Awakening was taking place. Manifestations of the Holy Spirit were, well, wailing, barking, and writhing, significantly, during worship services. These “signs” triggered the beginning of the Pentecostal movement, today one of the largest sects of Christianity. If the exact same behavior had taken place in a different context, the coverts would’ve been convicts.

It is safe to say that psychological explanations may be found for the bizarre activities of people living under a great deal of stress. No supernatural agency is required for glossolalia, spontaneous dancing, or canine vocalizations. If you look closely you’ll probably find any combination of the three in secular contexts during an average stroll through Manhattan. In a haunted country full of tales of the devil, they will be attributed to witchcraft. In a tent-meeting revival under the influence of an emphatic preacher, they will be called signs of the spirit.

Religions like to teach that they are universal, but in fact they are highly contextualized. What I used to tell my students about words applies also to acts—the meaning depends on the context. Whether somebody getting up off their ass is vulgar or merely a statement of fact depends on where the person is sitting. Religions are often rose-colored glasses, casting events in the shades we prefer to see. They are ways of interpreting the world around us and speculating on what, if anything, is outside our apparently closed system. There’s a lesson here to be learned by all. One person’s Monday may be another’s Thursday, but there’s no need for anyone to be crucified if they do it differently. Wouldn’t the world be a better place if we only believed that?