With all the buzz about the new Carrie movie just released, I decided to go back and watch the Brian De Palma version again. I’ve written here before about the religious symbolism of the movie, but I have to confess to never having read the novel. This time a particular symbol stood out, and I’m not sure whether it derives from De Palma or King. Crosses abound in the 1976 Carrie. This is a bit odd because of the indeterminate religion of Carrie’s mother. Clearly she has a belief in Jesus, but an odd Jesus it is. In Carrie’s prayer closet the statue—presumably of Jesus, since it is never clearly identified otherwise—is of a man whose abdomen in pierced with arrows. Those familiar with saints immediately recognize Saint Sebastian, but the arms are outstretched, as if this poor victim were both crucified and superfluously shot with arrows. The traditional cross, however, seems to be missing in that dark room. It reappears on prom night.

With all the buzz about the new Carrie movie just released, I decided to go back and watch the Brian De Palma version again. I’ve written here before about the religious symbolism of the movie, but I have to confess to never having read the novel. This time a particular symbol stood out, and I’m not sure whether it derives from De Palma or King. Crosses abound in the 1976 Carrie. This is a bit odd because of the indeterminate religion of Carrie’s mother. Clearly she has a belief in Jesus, but an odd Jesus it is. In Carrie’s prayer closet the statue—presumably of Jesus, since it is never clearly identified otherwise—is of a man whose abdomen in pierced with arrows. Those familiar with saints immediately recognize Saint Sebastian, but the arms are outstretched, as if this poor victim were both crucified and superfluously shot with arrows. The traditional cross, however, seems to be missing in that dark room. It reappears on prom night.

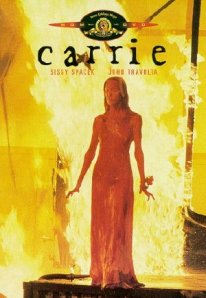

While Carrie is getting ready for the prom, her crazed mother peers out the window at passing cars, telling Carrie that Tommy isn’t coming. In one shot, as two cars pass in the street, there appears an inverted white cross on the road. I supposed at first that this was a painted parking space marker, but then, this is a residential street, and no such markers appear in other shots. Carrie’s mother had accused her of being a witch, and the upside-down cross is an oft-claimed symbol of Satanism (not the same, however, as Wicca). At the prom, Tommy insists that Carrie vote for them as the prom queen and king. When Carrie makes her x, the camera angle rotates slightly to reveal the sign as a Latin, as opposed to Saint Andrew’s cross. After Carrie kills everyone and goes home, her mother stabs her and, chasing her through the kitchen, makes the sign of the cross with her knife. Finally, Sue—in a dream?—wanders to Carrie’s burnt down house to lay flowers at the foot of a “for sale” sign that is a white cross, with the clashing words “Carrie White Burns in Hell” scrawled on it.

I may have missed more since the use of the symbol only dawned when the passing cars pointed me toward it. There is a strange kind of misuse of the cross here—not visible on the Sebastian-Jesus, and ultimately also Carrie’s mother figures, but inverted on the street, a sign of pride at the voting, made with a knife by the mother, and scrawled with an arrow pointing to Hell in the final scene. Carrie’s fiery end appears to confirm her mother’s interpretation of telekinesis as witchcraft. There is no forgiveness in this film. Well, I suppose I’ll have to go see the remake now. And maybe even read the book. I need to know if I’m just seeing things or if I’m still sleep-deprived from worrying about jobs and a surfeit of imagination as October’s chill settles in.