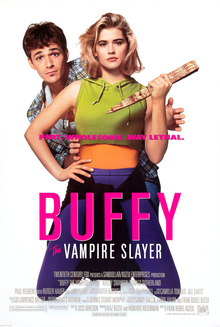

I have a confession to make. I had never, before just recently, seen any of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. This is kind of embarrassing because it was being talked about even as I was just starting to teach at Nashotah House. And it has been discussed in religion and horror books quite often. I understood that the television series was considered better than the original movie, but I felt that it was important to go to the source, at least to start. Joss Whedon, it is reported, distanced himself from the film he wrote because it began taking a different direction than he’d envisioned. The television series, which was praised among any number of critics, was more what he had in mind. Still, the film isn’t terrible. The concept of a ditzy blonde being an unwitting vampire hunter is entertaining and Kristy Swanson plays a pretty good Buffy and Donald Sutherland a great Merrick.

Having not seen the series to compare, the movie stands fairly well on its own. Vampire comedy horrors can be quite entertaining. The plot here is a bit overwrought and the love story feels tacked on to the vampire narrative. It lacks the strong through line characteristic of Joss Whedon movies. So, Buffy doesn’t realize that she’s a slayer, a kind of reincarnated vampire hunter. Merrick convinces her by telling her what her dreams have been. And Buffy has preternatural abilities—reflexes beyond human reach. And the vampires have been awaking in Los Angeles. The story just doesn’t hold together as well as it should. I was a bit surprised, however, to find the Bible quoted a time or two.

The charm, which also led me to read about Abraham Lincoln as a vampire slayer, is the unexpected juxtaposition. A cheerleader, or the best president we’ve managed to elect in this divided country, and vampires? Even more, vampire slayers? Vampires, although monsters, are often symbolic and sometimes sympathetic ones. Buffy’s vampires aren’t charming. Sometimes funny, yes, but they aren’t the tormented souls that elicit human sympathy. And Buffy adds its own backstory mythology. In Dracula Van Helsing was a mortal aware of vampire habits. Buffy sees this as a predetermined role, specifically female in nature. I’m not sure if I’ll be able to carve out the time to watch the television series. But at least, at this point, I have been able to put a bit more flesh on the character of an unlikely vampire foe. It only took me thirty-three years.